On Sunday mornings, the church bells of Matamoros crossed the Rio Grande to my hometown, Brownsville, Texas, like a distant voice trying to awaken a sleeping house. Sometimes the sound was faint and distant; other times, it cut through the sky like a blade—always as a reminder that two worlds were not separate, but interwoven by sound, smell, and memory. Occasionally, the Mexican army conducted drills, and their marching cadence rolled across the plains like thunder from below. Those bells and those boots became the soundtrack of my childhood: ceremonial and everyday, solemn and vibrant.

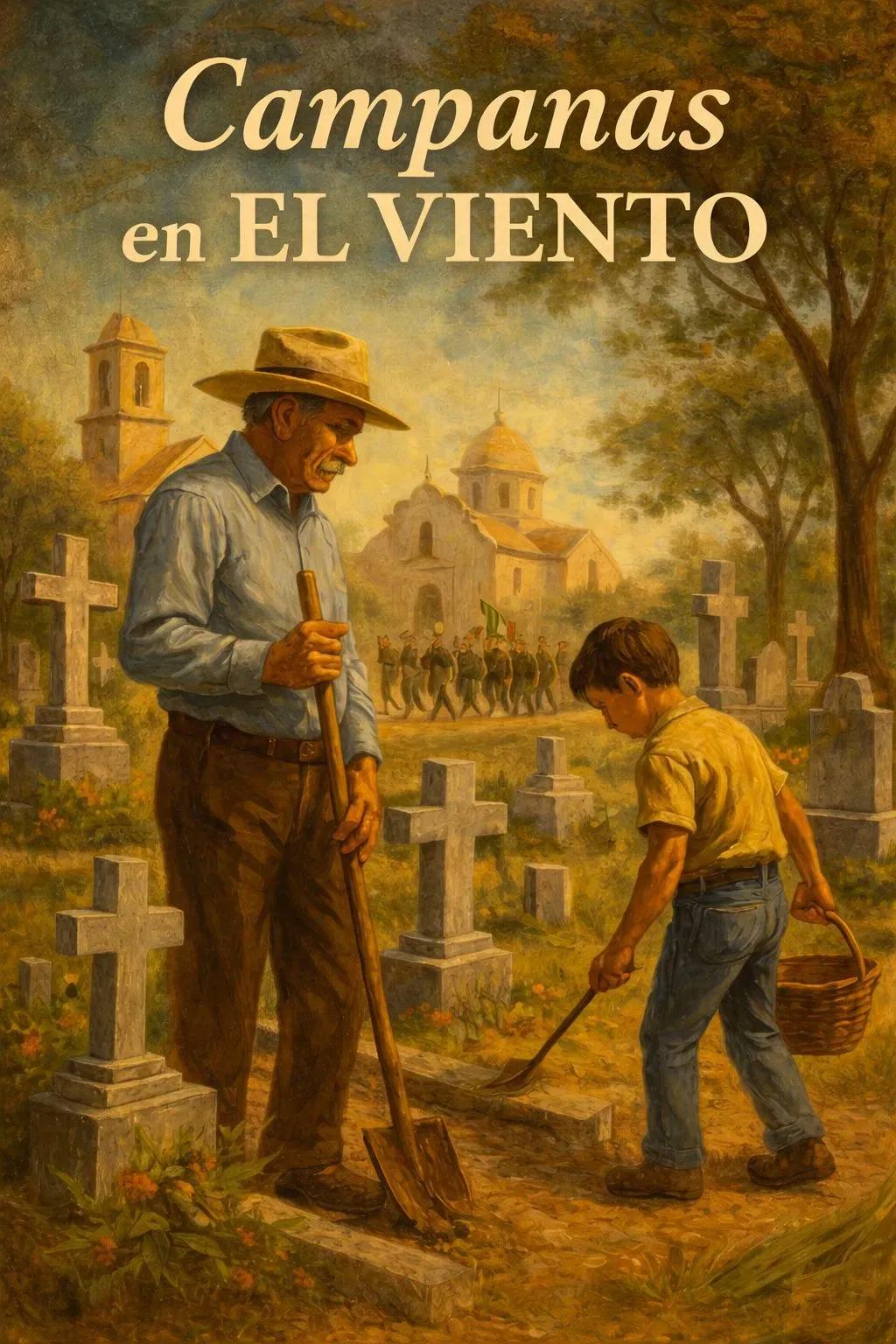

Some Sundays I went with my grandfather to the municipal cemetery in Brownsville to tend to my great-grandparents' graves. We hardly spoke. There existed between us a language that needed no words: a deliberate silence as we worked with small tools and hands that knew the contours of memory. We pulled weeds, swept up the trash that the Gulf winds left in their carelessness, straightened sun-faded frames and plastic flowers worn by time. It was a small, private liturgy, and the work itself felt like an act of devotion.

Today, looking back, I see what as a child I could not understand: that work was therapeutic for my grandfather. The cemetery offered him a task that quieted the noise of the world. It gave him order, continuity, a way to honor the people who had shaped his life. His movements were firm, almost meditative, as if each stubborn root he pulled loosened some inner weight. I think he enjoyed having company, not to converse, but for the shared responsibility. That’s how I learned that presence doesn’t always announce itself; sometimes it’s just two figures under the sun, doing what needs to be done.

When we finished our work, the reward came. We would go to the neighborhood tortillería, where the air was thick with steam and masa, and we would collect packages wrapped in paper, still warm to the touch. There we would buy barbacoa—meat slow-cooked in a pit underground, sometimes for twenty-four hours—tender, smoky, made to be shared. Back home, the table filled with tortillas, hot sauce, and lime. We ate until our hands gleamed, until the barbacoa was nothing but bones and memory, until the silent work of the cemetery gave way to laughter and the fullness of food. Those Sundays smelled of earth, firewood, and hot corn; they tasted like family.

There is a special peace in caring for places that are supposed to be still. Perhaps that’s why the cemetery became one of my favorite Sunday spots: the tasks were simple and honest, the movement repetitive and clear. In that silence, one hears things more vividly—the wind among the trees, a distant radio playing a bolero, the gentle sweep of a broom on concrete. Those sounds are not empty; they are the constant punctuation of a life that is preserved, that is remembered. Sometimes, the bells from across the river would filter in, intertwined with the roll of boots and the rustle of leaves. I learned to listen for what remains.

Now I am the only one who knows exactly where my ancestors’ graves are. The maps live within me, etched in memory.

No tombstone tells everything, but I remember. I carry their names, their resting places, their stories. Perhaps that’s why writing this text is also therapeutic for me. The act of remembering with words is not so different from sweeping a grave: both are gestures of care, ways of saying you are not forgotten. If the cemetery calmed my grandfather, the page quiets me.

Sometimes I wonder if someday, long after I am gone, a great-grandchild of mine will find this and read it. Perhaps they will recognize themselves in it, or at least catch a glimpse of who I was and who our ancestors were. Maybe they will understand that Sundays were not just days of rest, but days of memory—days when bells rang, armies marched, graves were tended, and barbacoa was pulled steaming from the earth for a family gathered around the table. If they search for where we came from, I hope they find us here: in the work and the food, in the silence and the singing.

Those Sunday rituals lodged in my chest and grew there. Later, when my life took darker currents, when violence, law, and interdiction work marked my days, I never lost sight of the double truths of the border territory. Mexico was music and golden light of dust; it was also danger and resistance. It was my grandfather’s patient hands, the silence of a cemetery, the metallic sound of army boots, and the smoky sweetness of barbacoa. The contradictions did not cancel each other out; they taught me to live within complexity without turning away.

Even today, the bells of Matamoros live in me like a refrain. When I close my eyes, I feel the roughness in my palms and hear the silence among the gestures in the cemetery. Memory is not tidy. It mixes the mundane with the profound until they become indistinguishable: the slow sway of a bolero, the brush of a broom, the crinkle of butcher paper wrapping hot tortillas. Those are the things that anchor me.

That’s how my Sunday mornings began, with the small, constant work of being present: caring, remembering, eating, listening. If the border taught me anything, it is that the sense of belonging is not always loud. Sometimes it resembles a quiet morning with a grandfather among headstones, followed by a meal that restores everyone at the table. Sometimes it is simply the hope that one day, when our turn comes, someone will pass by, sweep the place—and remember.

Leo Silva is a former resident agent in charge of the DEA (Resident Office in Monterrey) and author of The Reign of Terror, with decades of front-line experience in the fight against transnational cartels.

Since the publication of his memoirs, Silva has become a recognized voice in the media and speaking circuit. His story and analyses have been featured in interviews with Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jorge Ramos on Univision (This Is How I See Things), three-time Emmy winner Paco Cobos (The Interview), and Ana Paulina (Voices with Ana Paulina), where his participation garnered millions of views. He has also been invited to prominent platforms such as the Cops and Writers podcast with Patrick J. O’Donnell, Game of Crimes with Steve Murphy, and Called to Serve with Roberto Hernández.

Through his books, lectures, and media appearances, Silva continues to shed light on the realities of organized crime, law enforcement work, and the human cost of the war on drugs, while sharing lessons on resilience, leadership, and truth.

Comments