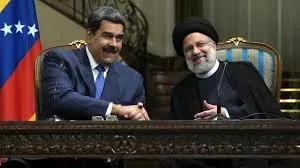

The Iranian president, Ebrahim Raisi, on the right, and his Venezuelan counterpart, Nicolás Maduro, shake hands at the end of their joint press conference at the Saadabad Palace in Tehran, Iran, on Saturday, June 11, 2022. © Vahid Salemi / AP

Power, in its rawest form, does not rest solely on force, but on a complex structure of artificial legitimacies, transnational support networks, and carefully maintained fictions. Nicolás Maduro does not govern Venezuela: he manages it from a regime that has mutated into an autopoietic machinery of authoritarian reproduction. Asking if he can "fall" is equivalent to interrogating the very heart of the hybrid model that amalgamates despotism, electoral façade, and convenience international alliances. In this board, Venezuela does not play alone: it is precisely the movement of its allies—Iran, Russia, and China—that might open, for the first time in years, a significant crack in its armor.

An asymmetrical trident: Caracas, Tehran, Moscow

The geopolitics of chavismo is, above all, a politics of survival. Its alignment with the three major counterweights of the Western liberal order must be read through this lens. Maduro's regime has consolidated a model of dependency diplomacy: oil for loyalty, gold for arms, international legitimization for control technology.

Iran provides military training and sophisticated civil repression tactics (the "Basij model" adapted to the Venezuelan urban context), along with opaque cooperation in refineries and oil smuggling. Russia, for its part, acts as a guarantor of strategic stability: it finances, supplies arms, and—above all—blocks resolutions in multilateral forums that could escalate into effective sanctions. China operates as a silent banker and long-term strategist: its interest lies in lithium, oil, and a key position in the American periphery.

But there is something more subtle: these three actors, each in their own way, support Maduro not only as an ally but also as a symbol. In a fractured world, the continuity of the Venezuelan regime serves as a poke in the eye for the West, a testament that the time for "regime change" has become obsolete as a doctrine.

What sustains the regime beyond oil?

The post-oil chavismo economy—because yes, chavismo survived the decline of PDVSA as a power—has been reconfigured into a blend of illicit economies, clientelistic networks, and an informal dollarization that sustains the most affluent sector of the government. The regime's support is, today, more “extraterritorial” than national: organized crime, links with Hezbollah, triangulation with the Iranian regime, and drug trafficking routes controlled by sectors of the state configure a model of political-financial support that analyst Moisés Naím aptly termed as “the criminal state.”

This configuration is not an accident but a structural adaptation. Venezuela is no longer a rentier economy but a criminal enclave economy with an institutional façade. Its persistence no longer depends so much on the price of crude oil as on the continuity of those external links that provide logistics, legitimization, and repressive know-how.

Iran: Achilles' heel?

Seldom is the stability of Caracas connected with the ups and downs of Tehran. However, the link is not negligible. Iran is not just a diplomatic ally: it is a strategic provider of energy infrastructure, clandestine logistics, and repressive advisory. The internal collapse of the Iranian regime—before a hypothetical transition, revolution, or regional defeat—would not only weaken this alliance but would also contrast the isolation of Maduro in an increasingly reconfigured world by new alignments.

The question then is not simply “Can Maduro fall?”, but “What needs to fall for Maduro to fall?”. In that equation, Iran appears as a crucial node of power. If the Tehran-Caracas axis is dismantled, one of the regime's vital flows is interrupted: that of operational advice and illicit financial circulation. It is no coincidence that moments of greatest tension in the Middle East coincide with a reinforced discourse from the Venezuelan government: distant wars have immediate effects in the Miraflores Palace.

Electoral process, opposition, and democratic fiction

The Venezuelan regime has perfected an electoral system in which the act of voting is a ceremony drained of political efficacy. Recent attempts by the opposition to articulate a unified force have collided with a manipulated electoral machinery, a co-opted judicial system, and a repressive apparatus that neutralizes dissent before it can even form. The exclusion of candidacies like that of María Corina Machado is not an institutional error: it is the internal logic of the “competitive authoritarianism” model, as Levitsky and Way describe, in its most brazen version.

The opposition, divided, demoralized, and often co-opted, serves as a sparring partner for the regime. Chavismo needs the opposition to exist, but it should never win. This equilibrium is maintained thanks to international shielding that ensures the collapse does not escalate into intervention and that repression does not provoke a coordinated global reaction.

Regimes sustained from outside: comparative lessons?

The history of the 21st century has shown that authoritarian regimes survive not due to internal strength but through functional external alliances. North Korea without China would not exist. Syria without Russia would have fallen a decade ago. Cuba without Venezuela would have imploded. Venezuela, without Iran and Moscow, would no longer be what it is. Autarky is dead: even the most closed regimes need the international system, even if only to subvert it.

In that sense, Maduro is more a symptom than a cause. He represents the capacity of authoritarian regimes to adapt to the global system, operate in its shadow, and survive thanks to their structural cynicism. The regime has learned to negotiate sanctions, exploit diplomatic fissures, and seduce those who prefer business over principles.

Is checkmate possible?

Venezuela will not collapse from within. It will not fall due to citizen pressure or "free" elections organized by those who guarantee its opacity. The eventual “checkmate” to Maduro could only come from a rupture in the larger board: a collapse of its external alliances, a financial implosion of its support networks, or a regional recomposition that makes it expendable to its partners.

But even then, the fall is not a guarantee of a democratic transition. The structures of chavismo transcend Maduro. The problem is not only the man but the system that engendered him, sustained him, and—if he falls—is likely and capable of mutating again.

Ultimately, the question is not just whether Maduro can fall, but whether the world wants that to happen. Because in a fragmented, unstable, and cynical world, regimes like his are not an anomaly... they are a warning.

Comments