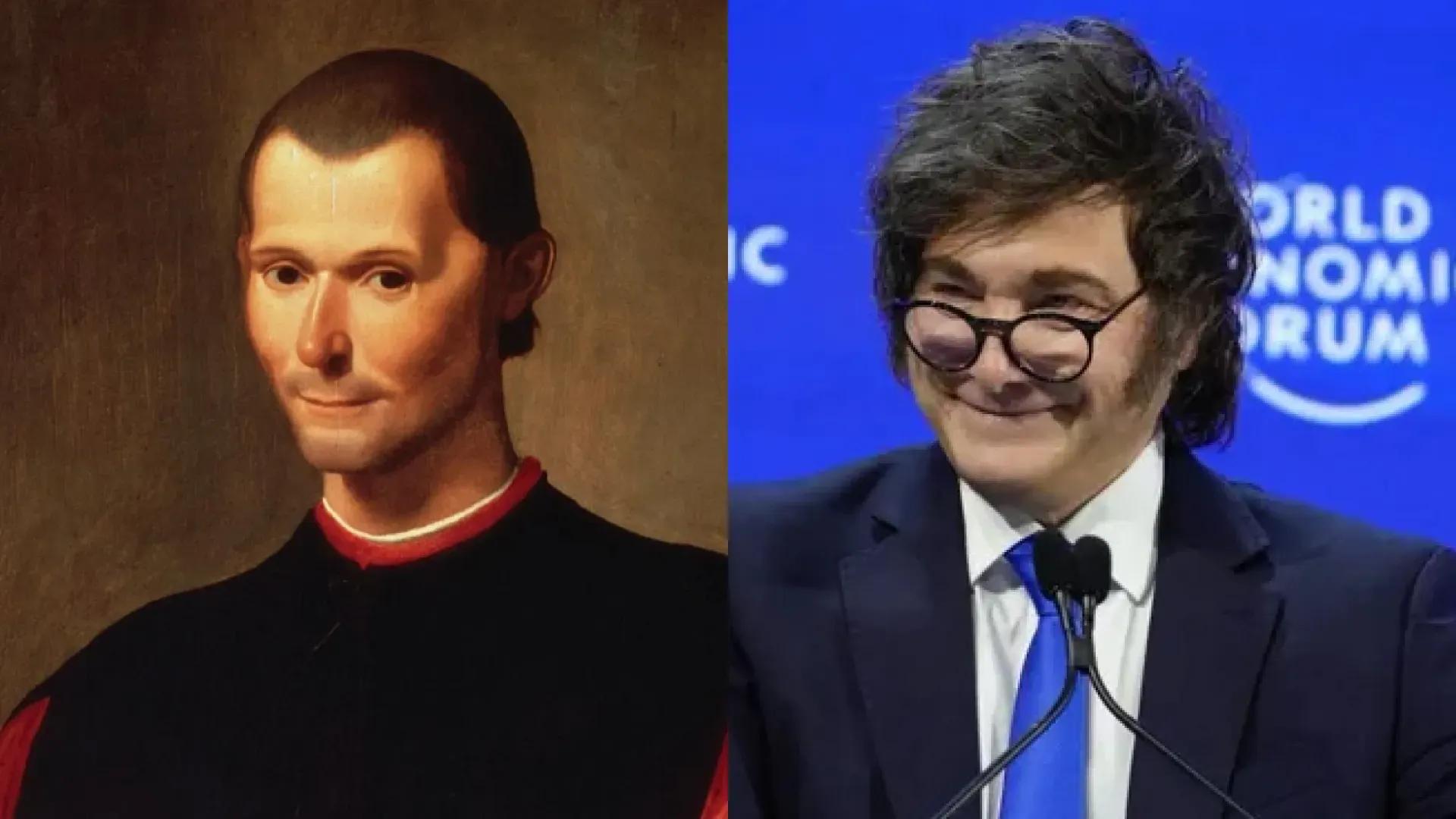

In his presentation at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Javier Milei once again used one of his high-voltage conceptual phrases: “Machiavelli is dead”. The declaration was neither casual nor isolated. It appeared within the framework of a speech aimed at questioning the political, economic, and cultural consensuses that —according to his viewpoint— have dominated the West for the last few decades.

The context is key. Milei spoke before political leaders, businesspeople, and officials from multilateral organizations, an audience historically associated with pragmatism, diplomacy, and constant negotiation. That is to say, at the very heart of the politics he comes to challenge. In that setting, declaring the “death” of Nicolás Machiavelli functions as a calculated provocation: it does not aim at the Florentine thinker himself, but rather at what he represents in contemporary political practice.

Machiavelli symbolizes the politics of calculation, balance, and possible agreements even at the cost of principles. Politics understood as a technique for managing power, where morality is subordinated to efficacy. By saying that this model is dead, Milei asserts that this scheme no longer organizes current reality: neither in Argentina nor, according to his diagnosis, in the world.

In the Davos speech, the phrase is inscribed within a broader narrative: the rejection of gradualism, political correctness, and what he calls “artificial consensuses.” For Milei, politics has ceased to reward moderate leaders and has begun to validate those who express a clear, confrontational, and unnuanced ideological position. In this sense, the assertion seeks to legitimize his own style: frontal, disruptive, and openly conflictual.

There is also a message directed at the global elites. Milei suggests that the political-economic order that Davos helped to consolidate —based on multilateral agreements, cross-regulations, and constant negotiation— is in crisis. In his view, the stage opening is one of sharp definitions, where ambiguity no longer builds power but rather social distrust.

However, the phrase contains a paradox. Although Machiavelli's end is declared, the exercise of power still requires strategic decisions, tactical alliances, and conflict management. The difference is that Milei does not renounce power, but rather the traditional language with which it is exercised.

In Davos, when he said “Machiavelli is dead,” Milei was not engaging in political philosophy: he was drawing a line. Between politics justified by cunning and that legitimized by conviction. Between the order negotiated in silence and that imposed in full view of everyone. For his followers, it is a sign of the times. For his critics, a warning about the limits of governing without pragmatism.

Comments