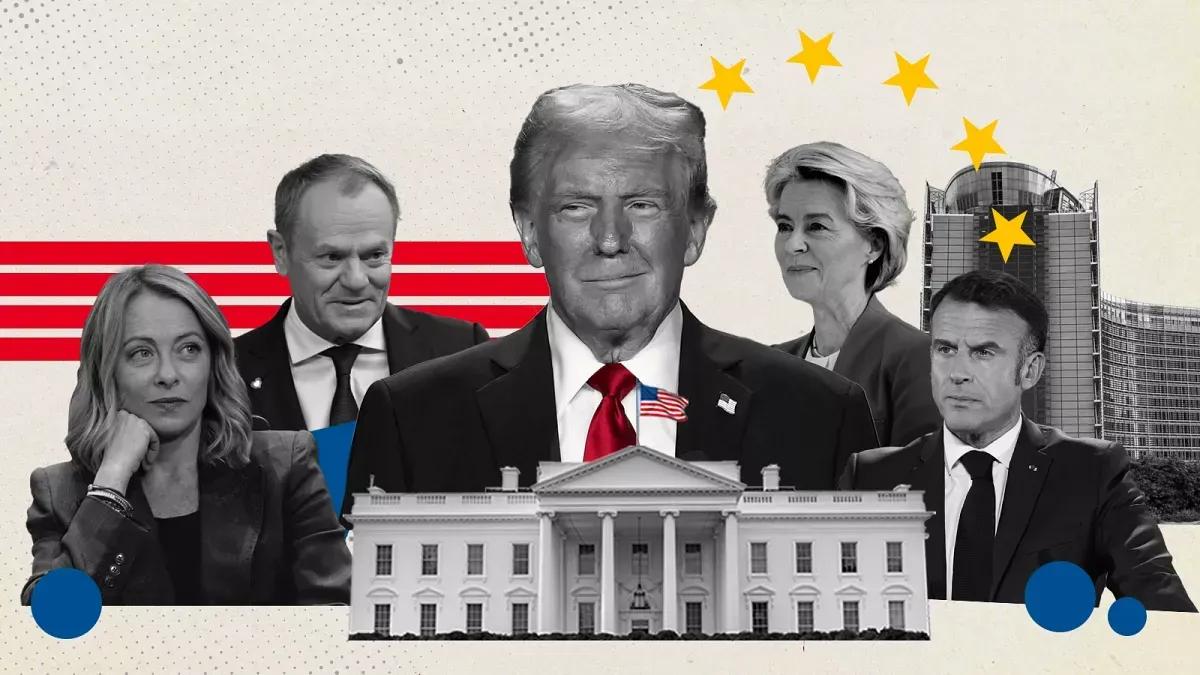

Donald Trump has begun his second presidential term with a worldview that explicitly breaks with the basic consensuses that have structured the international system, with varying degrees of coherence, since the end of World War II. This shift is not merely rhetorical or circumstantial; it affects the very foundations of the liberal order built around multilateral institutions, stable alliances, and shared norms, pillars upon which Europe has based its security and prosperity for over seven decades. For the Republican president, the United States faces an existential threat: the potential loss of its global primacy to the sustained rise of China, the strategic challenge posed by Russia, and, increasingly explicitly, the economic and regulatory competition from the European Union, which had until now been considered a natural ally.

Under the slogan of making “America great again”, Trump has deployed an aggressive foreign policy, based on economic pressure, the instrumental use of trade tariffs, and the logic of faits accomplis. In his view, there is no longer a clear distinction between historical allies and geopolitical adversaries: all are subjected to a strictly utilitarian calculation of costs and benefits. The result is an increasingly belligerent international climate, characterized by the militarization of international relations and the revival of arms races that evoke the darkest tensions of the 20th century.

Trump himself made this vision explicit in his inaugural speech, where he announced openly expansionist ambitions. The idea of turning Canada into the 51st state of the Union, the appropriation of Greenland, and the regaining of control over the Panama Canal — with the declared objective of displacing Chinese operators from this strategic enclave of global trade — were not mere rhetorical provocations, but signals of a deep doctrinal shift. Underlying these ideas is a conception of international power based on force and territorial domination, in blatant contradiction with the principles of contemporary international law.

Trump has not hesitated to use tariffs as a weapon to force NATO countries to increase their defense spending, directing it preferentially toward the purchase of American weapons. Likewise, he has authorized direct military actions against Iran, with the argument of putting an end to the so-called war of the thirteen days with Israel, and has promoted operations in Venezuela with the dual objective of capturing President Nicolás Maduro — whom he accuses of drug trafficking — and securing control over the largest proven oil reserves on the planet.

These policies have generated tensions in multiple regions of the world, but their impact has been particularly corrosive in Europe, the main strategic ally and trading partner of the United States since 1945. Washington seems to have forgotten not only the shared history but also the dense web of interdependencies that includes dozens of American military bases on European soil and nearly 80,000 permanently deployed personnel.

The marginalization of Europe from major international negotiations has become a constant. European governments have been excluded from key engagements regarding a potential negotiated exit from the war in Ukraine, the redesign of the balance of power in the Middle East following the conflict between Israel, Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran, the future of Gaza, and discussions about neutralizing the Iranian nuclear program. For Trump, traditional alliances are a burden if they do not produce immediate and quantifiable benefits.

The world that the American president imagines is, in his own words, a scenario “governed by force, governed by power, governed by domination.” This vision unsettlingly evokes the Hobbesian conception of the state of nature, where man is the wolf of man and the absence of a higher authority turns violence into the norm. In the international arena, this logic translates into the normalization of the impunity of interventionism: extrajudicial attacks, regime changes, privatization of peace, and systematic disregard for multilateral mechanisms.

In doing so, Trump has explicitly abandoned the principled tradition of American foreign policy, which was based — at least on the rhetorical level — on the defense of democracy, the self-determination of peoples, and human rights, a vision promoted by presidents such as Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, or Jimmy Carter. He even surpasses the classic realism of figures like Hans Morgenthau, Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger, or Ronald Reagan, who, despite their pragmatism, recognized the need for shared rules to avoid systemic chaos.

In this context, Trump has revived a deeply controversial doctrine from the 19th century: the Monroe Doctrine, formulated in 1823, and especially its imperialist reinterpretation at the beginning of the 20th century, known as the Roosevelt Corollary. On September 2, 1901, Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed his famous maxim: “Speak softly and carry a big stick, you will go far.” This motto justified decades of American military interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean to protect the interests of its companies.

Trump has updated that legacy under what numerous analysts ironically call the “Donroe Doctrine.” Its objective is clear: to make Latin America an exclusive sphere of influence for the United States, closed off to the economic and technological expansion of China. This strategy has strained relations with Latin American governments and reinforced the perception of a return to the harshest form of imperialism.

Simultaneously, the American president has demanded that Denmark and the European Union cede Greenland, a Danish autonomous territory and historical ally within NATO. Threats of differentiated tariffs and the explicit use of military pressure have called into question the very survival of the Atlantic Alliance. For Trump, controlling the Arctic, its future trade routes, and its vast natural resources — including rare earths — justifies any political cost. Furthermore, incorporating Greenland would make it the largest territorial acquisition made by any American president and would turn the United States into the country with the largest land area on the planet.

The war in Ukraine is another central point of friction. While the Trump Administration seeks a quick exit from the conflict, even at the cost of territorial concessions and security guarantees for Moscow, the main European countries maintain a much tougher stance. France, Germany, Poland, Finland, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Italy are managing intelligence reports that anticipate a direct confrontation with Russia by 2030. According to these assessments, Moscow produces more tanks than it needs, reorganizes its army, creates new military districts oriented toward the West, and reinforces its navy.

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte has even compared the current scenario to the world wars of the 20th century. “We are the next target of Russia,” he stated in December in Berlin. In countries with a historical memory marked by Russian invasions, the threat is perceived as particularly real. According to data cited by journalist Marc Bassets in El País, 77% of Poles consider the risk of an attack in the coming years to be high or very high; in Spain, that perception reaches 49%.

Faced with this scenario, Europe has opted to buy time. It supports Ukrainian resistance through loans and supply of weapons while accelerating its own rearmament and debating the reestablishment of compulsory military service. The goal is twofold: to wear down Russia and prepare for a potential direct conflict, even at the price of prolonging a war that is largely fought to the last Ukrainian.

In economic terms, Washington's tariff threats have pushed the European Union to progressively reduce its dependence on the dollar. The euro gains ground as a reference currency, while Brussels diversifies its trade links through agreements with Mercosur, India, and China. At the same time, Europe has shown caution toward Trump's diplomatic initiatives: with the exception of Hungary and Bulgaria, no significant European country has joined the Peace Board for Gaza promoted by the White House.

Conclusions

Paradoxically, Donald Trump's foreign policy has achieved an effect that few would have anticipated: it has strengthened the internal cohesion of Europe and accelerated its transformation into a geopolitical actor more aware of its vulnerability and the need for strategic autonomy. By treating the continent as a dispensable partner and subjecting it to constant pressure — commercial, military, and diplomatic — Washington has pushed the European Union to rethink its place in the world, invest in its own defense, and seek a voice of its own in an increasingly hostile international arena.

However, this process unfolds in an extraordinarily dangerous context. The deliberate abandonment of international law rules and the return to a logic of naked power place the world on the brink of a new era of conflicts, marked by expansionism and the normalization of territorial conquests. In this sense, the current situation unsettlingly evokes Europe in 1938, when the weakened and divided democratic powers looked on with a mixture of fear and resignation at the advance of a policy of faits accomplis.

Then, as now, pragmatic calculation and the desire to avoid immediate confrontation led to the acceptance of the progressive erosion of the existing order. The Munich Agreements, presented at the time as a guarantee of peace, ended up legitimizing a logic according to which force prevailed over law and borders could be changed through threats or the use of violence. The result was a catastrophe of historical dimensions.

The analogy is not mechanical, but it is instructive. Today, as on the eve of World War II, Europe faces the dilemma of resigning itself to a world governed by the law of the strongest.

Adalberto Agozino is a Doctor in Political Science, International Analyst, and Lecturer at the University of Buenos Aires.

Comments