What happened in Venezuela on January 3rd is a case of unilateral interference, this time exercised by a state and not to safeguard a greater good such as the security of the Venezuelan population. In other words, without any discussion, it was an act of force by one state over another based on a requirement of justice from the first.

The issue regarding interference gained prominence in the 1990s following the U.S. intervention in Kuwait to expel Iraqi forces that had invaded the Gulf petromonarchy.

Thus, in order to safeguard the population in northern Iraq, in April 1991 the UN Security Council approved Resolution 688, which condemned Hussein's repression of Kurds and Shiites in Iraq and established a no-fly zone to fulfill this humanitarian purpose.

In this way, it became clear that in certain interstate situations, the protection and assistance of peoples took precedence over one of the great principles of international law: non-intervention in the internal and external affairs of states.

From that point on, it seemed that the so-called "institutional model" in international politics, that is, the primacy of law and norms among states, was starting a cycle that would favor an international order directed beyond the exclusively interstate, perhaps toward what Hedley Bull referred to as "world order," that is, issues within the states.

The end of the Cold War regime, the rise of "images" related to the advent of a world founded on geo-commercial blocs, the expansion of "UN missions," and the formation of a coalition of almost thirty countries to expel the Iraqi autocracy from Kuwait served as events that credited a new international order. President George H. Bush himself referred to a new scenario in which a more equitable distribution of international justice would prevail.

Finally, at the beginning of the 21st century, the UN promoted the Responsibility to Protect principle, an initiative aimed at protecting peoples whose security ceased to be guaranteed by the state to which they belonged.

The multilateral right of interference and the responsibility to protect were not only applied in different conflicts and situations, but the interference also had a multidimensional character in terms of security, meaning it could be applied in various issues: from those related to nuclear insecurity due to the state's incapacity to ensure the "securitization" of nuclear complexes to those related to collapsed countries.

However, nothing (or almost nothing) in interstate politics is neutral: interests often come before altruism or a commitment based on aspirations guided by pacifism, even when the interference is grounded in authorized multilateral action.

For instance, in Kadafi's Libya, the multilateral intervention (authorized by the UN Security Council through resolution 1973) was to protect the population trapped in the turmoil. But once the intervention commenced, the purpose shifted to supporting forces opposing Kadafi, with the well-known outcome and the consequent geopolitical fissure of the North African country, which continues to this day.

What recently happened in Venezuela reframes interference but in a categorically unilateral key, that is, a procedure carried out by a state with greater capabilities that "jumps" all the norms in the name of its national interests and security. It was a precise moment in which a powerful actor broke away from complying with the international norm to safeguard its national interest.

As we said, the interference in Venezuela was not to protect any greater good as has happened with multilateral interference in other scenarios (although there were also cases of multilateral interference without Security Council authorization) but rather to capture and extradite the president of a highly questioned regime in order to bring him to American justice to face charges of being part of organized crime.

Of course, this type of interference never takes place in anti-geopolitical sites, that is, areas of the world that do not concentrate strategic assets, but in zones marked by significant geopolitical control of major and intermediate powers, such as Central America, the Caribbean, or Eastern Europe and the Caucasus (North and South), among the main ones. Places where the regional hegemonic power is unlikely to tolerate regimes whose purposes and actions extend beyond what is acceptable to it.

These strategic assets are of multiple natures, that is, the "old assets" and the new assets, namely, a "vademecum" of key minerals for the development of major technologies, such as silicon, lithium, manganese, and the "bag" of minerals containing rare earths, among others.

Thus, we are rapidly advancing toward a scenario centered on what Brazilian Helio Jaguaribe termed "supply imperialism," something itself unsettling, accompanied by an environment of increasing interference without multilateralism.

The strategic context or higher level where this interference is deployed or redeployed is the rivalry between the United States and China, the new bipolarity shaping international politics in the 21st century. And the American interference in Venezuela was the categorical proof: denying (this verb is central to understanding the American approach toward its rival) sources of resources to China.

Although it hasn’t been widely reported, the impact reprisals from Beijing, primarily geoeconomic, were considerable and demonstrate the notable construction of added power and capacity to project influence by the Asian power.

However, this (new) American containment of China is just one of several, as, in parallel to geoeconomic containment, Washington is deploying others of a military, technological, geoeconomic nature, to name the main ones, an event that casts doubt on the world's trajectory toward a configuration based on rigid spheres of influence, while tending to affirm what is called “Pax Sílica” in the United States, that is, an initiative launched in December 2025 by this actor, joined by Australia, Israel, South Korea, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Singapore, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, which consists basically of ensuring that "critical supply chains are secure, prosperous, and innovative."

In the Declaration of Pax Sílica, it is clear that the challenge is China, as among the main purposes of the initiative is to: "Create resilient networks to avoid bottlenecks or single points of failure that may be exploited by external strategic actors, especially China, or by geopolitical crises."

Likewise, "Strengthen technological cooperation among allied countries to maintain the competitive advantage in AI and semiconductors."

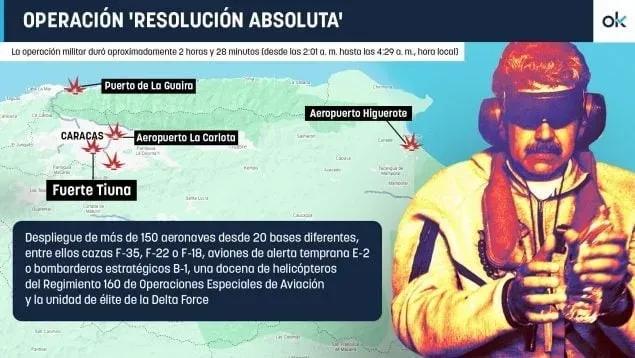

In short, with "Operation Absolute Resolution," the United States has blatantly violated the principle of non-intervention. It did so because it can; and this reality, that of the deployment and projection of national capabilities, is the main peculiarity of the current world along with the unprecedented decline of multilateralism.

A situation that cannot and should not surprise, as hierarchy, power, competition, capabilities, and distrust among states have been a regularity in history. What increasingly surprises and unsettles is the unstable condition of the very international disorder due to its confrontational state, that is, with powers bearing the conditions to configure an order in a state of confrontation and even of almost war.

By Alberto Hutschenreuter

Alberto Hutschenreuter, is a Doctor in International Relations (summa cum Laude, USAL). A full professor of Geopolitics at the Higher School of Air Warfare. He has taught at the University of Buenos Aires and directed the Eurasia Space Cycle at UAI. Director of Equilibrium Global. Author of the book “Russian Foreign Policy After the Cold War: Humiliation and Reparation” (2011). Co-author of the book “International Debate. Current Scenarios” (2014). He has written numerous papers in national and foreign media.

Comments