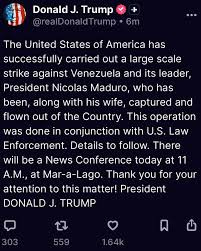

Yesterday, a photo of Maduro handcuffed on a plane was posted from Trump's account.

No one saw him arrested on the street. There was no live coverage of the operation. There is no record of any legal process. Just an image and a tweet.

And yet, the price of oil moved. Markets reacted. Governments issued statements. The media covered "the event."

What event? Maduro's arrest or the tweet's publication?

This is where most of the analyses I've seen these days fall short. Because they insist on asking: is it true or false? Is he really in prison? Is it a setup?

Wrong questions for the phenomenon we are witnessing.

The CCRU and Productive Fictions

Back in the late nineties, a group of academics at the University of Warwick formed what they called the CCRU: Cybernetic Culture Research Unit. Among them were Nick Land, Sadie Plant, Mark Fisher, and others who would later become influential in contemporary theory.

One of their central ideas was the concept of hyperstition: fictions that make themselves real by being narrated and believed.

It’s not the same as a lie. A lie presupposes a truth that is being hidden or distorted. Hyperstition operates differently: it does not hide anything, it produces something.

It is also not the same as a common self-fulfilling prophecy. It is more than that. It’s about understanding that certain narratives function as productive machines that generate the material conditions for their own realization.

The Most Obvious Example We Don’t See

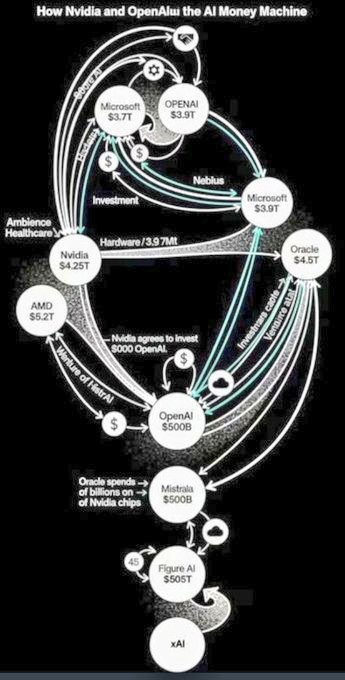

Think about money, currency, the little bills, the cash.

A one-hundred-dollar bill is a piece of paper. It has no intrinsic value. You can't eat it, it doesn't keep you warm, it doesn't heal you. Its parity with gold was removed decades ago. And yet, it works as if it had value. Why? Because we all act as if it does.

Money is a successful hyperstition. A shared fiction that, by being shared, produces absolutely real effects: it moves goods, builds buildings, finances wars, feeds populations.

It makes no sense to ask if the value of money is “true” or “false.” The question is obsolete. Money works. It produces reality.

Let’s Go Back to Maduro

With this in mind, let’s take another look at what happened.

Trump posts a photo. He says Maduro was arrested. Markets react. Governments respond. The media covers.

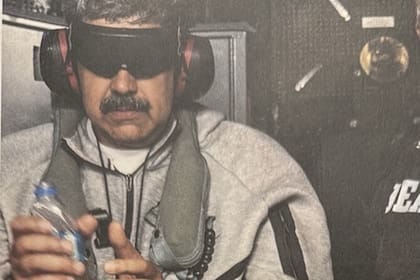

Does it matter if Maduro is “really” imprisoned in any verifiable sense? The photo has already done its job. It has already produced capital movements, geopolitical repositioning, narratives that will structure the upcoming weeks of coverage, and it also made Nike break sales records with the outfit that the hardest one wore.

The tweet was not a report about an event. The tweet was the event.

This is not a conspiracy theory. I’m not saying that “they are lying to us.” I’m saying something more evident: that the distinction between truth and lie, between real and false, has ceased to be referential for understanding these phenomena.

Why Our Categories Don’t Work

When we see something like this, our instinct is to grab the moral compass: who are the good guys? Who are the bad guys? Who tells the truth? Who lies?

Good-bad. Victim-victimizer. True-false.

These are categories of the nineteenth century. Tools designed for a world where propaganda worked by hiding information, where there was a reality “out there” that power distorted, where critical work was to clear the fog to see clearly.

But today power does not operate by hiding. It operates by producing. It does not hide reality behind a smoke screen. It generates reality through the circulation of signs.

There is no truth hidden beneath Trump's tweet waiting to be discovered. The tweet is the thing. It is the productive machine doing its job.

So What?

This is where people usually ask: “Well, what do we do? Do we resign ourselves? Does everything go?”

No.

But we do need to change the questions we ask.

Instead of “What is true?”, ask “What does this narrative produce?”

Instead of “Who is right?”, ask “What material effects does this circulation of signs generate?”

Instead of “What is really happening?”, ask “What futures become more likely if this fiction becomes widespread?”

And perhaps the most important: What do we want to make real?

Because if fictions are productive machines of reality, then we must think about what fictions we are feeding, amplifying, circulating. Not from the naivety of believing that we can “tell the truth” against the lies of power. But from the understanding that we are all caught in a war of narratives where the prize is not being right but producing a world.

Final Note

I am not writing this to tell you what to think about Venezuela or Trump. I genuinely don’t care to get into that debate.

I write this because it frustrates me to see the same sterile conversation repeat every time something like this happens: “it’s true”, “it’s a lie”, “the media lies”, “we need to find real information”, “dude, that’s how socialism started”.

All of that presupposes a world that no longer exists. A world where there was a territory beneath the map.

Today the map is the only thing there is. And those who understand that are the ones drawing. We need to battle against the hyperstitional sorcerers of capital.

Comments