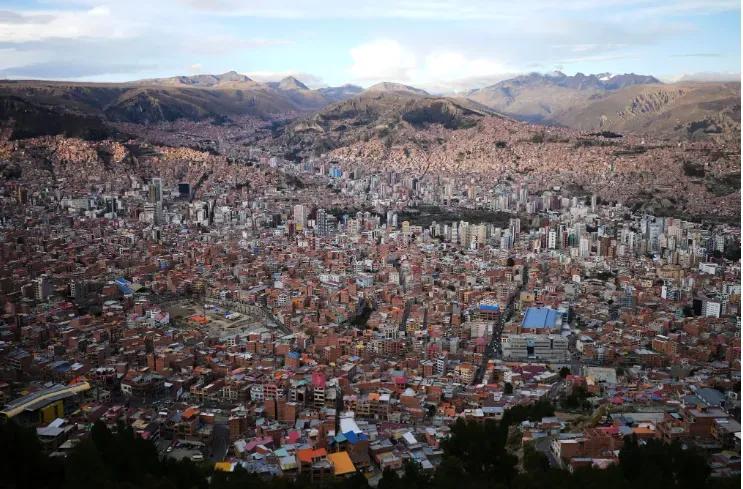

Bolivia at the End of a Cycle: Between the Fatigue of the Model and the Mirage of Consensus

Although history insists on presenting itself as a straight line, the truth is that Latin America advances in pendulum swings. Each oscillation—sometimes gentle, other times convulsive—redefines the contours of its politics, rewrites its ideological loyalties, and exposes the limits of its economic promises. Bolivia has just experienced one of those oscillations that set a precedent: the victory of Rodrigo Paz Pereira in the presidential elections of October 2025, marking the end of the hegemony of the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) and inaugurating a stage of uncertainty that condenses both the exhaustion of a cycle and the search for a new national narrative.

The Closure of a Political Era

Since 2006, Bolivian politics has been permeated by the grammar of MAS: a mix of economic nationalism, plebeian rhetoric, and state centralization that redefined the relationship between the state, territory, and resources. Evo Morales and then Luis Arce governed under the premise that the state was the great redistributor of the gas miracle. But the miracle has run out. The fall of hydrocarbon income exposed the structural dependency of the Bolivian economy, eroding the fiscal and symbolic bases upon which the "process of change" was built.

The collapse was not sudden, but progressive. The recession, the shortage of dollars, persistent inflation, and the loss of institutional trust transformed the state into an administrator of scarcity. In this framework, the defeat of MAS was not so much the result of an efficient electoral campaign by the opposition, but rather the manifestation of a collective exhaustion: the fatigue of a model that promised nothing more than its own survival.

Rodrigo Paz and the Return of Pragmatism

The rise of Rodrigo Paz Pereira, a moderate centrist, can be seen as an almost physiological reaction of the political system: when ideologies run dry, pragmatism emerges as a refuge. His motto of “capitalism for all” initially sounds like a calculated oxymoron, an impossible balancing act in a country marked by inequality and territorial fragmentation. However, it expresses something deeper: an attempt to reconcile the dynamism of the market with the need for social cohesion, an old Latin American aspiration often promised yet frustrated.

Paz's idea of “making money stretch when there’s no theft” is rhetorically effective and morally seductive, but it currently lacks structural anchoring. Governing a country in crisis requires not only austerity and public ethics but also a power architecture capable of sustaining unpopular decisions. And in Bolivia, that architecture is currently fragmented: no party has a legislative majority, and the internal fragmentation of political forces threatens to paralyze any attempt at substantive reform.

The Politics of Orphanhood

Thus, Bolivia enters a phase of ideological orphanhood. MAS leaves behind a void that is unlikely to be filled by centrist technocracy. For almost two decades, the narrative of sovereignty and national dignity had provided meaning to the popular classes and indigenous movements. Today, the appeal to “consensus” and “reconciliation” seems more a moral imperative than a political possibility. The memory of polarization remains alive: the fractures between the highlands and the east, between urban and rural areas, between the central state and the regions, are still open wounds.

In this context, Paz will have to govern a country that demands not only economic solutions but also a symbolic recomposition of the national pact. And therein lies the most complex challenge: reconstructing legitimacy in a society that has lost faith in both revolutionary discourse and technocratic language.

The Drift of Progressivism

The end of the MAS cycle is part of a broader regional phenomenon: the erosion of progressive projects that dominated Latin America during the first two decades of the 21st century. From Brazil to Argentina, from Chile to Mexico, the ideological pendulum has started to swing towards more hybrid positions, where the axis no longer lies in left or right but in the capacity to govern amid the collapse of the social contract.

Bolivia is not an exception; it is a laboratory of this transition. The dissolution of the rentier paradigm and the fatigue of economic populism create space for a new political grammar that still lacks a name. Perhaps we are witnessing the emergence of a “Latin American realism,” an attempt to manage the crisis without epic narratives, seeking stability in a continent accustomed to upheaval.

Economy and Legitimacy

The new Bolivian government will have to extinguish several fires simultaneously. The currency crisis, fuel shortages, and declining fiscal revenues are symptoms of an economy in a state of structural fatigue. With no room to borrow or capacity for major reforms, Paz will face the paradox of any government succeeding a prolonged regime: he will need to rebuild trust without resources.

The Country to Come

Bolivia stands at a point that transcends the electoral outcome. What is at stake is not only the management of an economic crisis but the redefinition of its political contract. Paz Pereira assumes power in a country that must learn to govern itself without a foundational myth: without Evo’s government, without the epic of change, without gas revenues.

Can a centrist leadership articulate a national narrative that does not depend on confrontation? Or are we witnessing a temporary truce before a new political explosion?

Ultimately, Bolivia's challenge is not economic or institutional, but existential: to believe again that the future can be built without heroes or enemies, only with citizens.

Comments