José Adán Gutiérrez and Rafael Marrero from Miami Strategic Intelligence Institute for FinGurú

This document analyzes how China’s food strategy abroad is transforming global trade, the security motivations underpinning it, and the implications for the United States. It also examines China’s attempts to acquire agricultural land in the U.S., which have raised significant national security concerns and prompted political responses.

China's food sourcing, both abroad and domestically, reflects a broader strategy to protect itself against geopolitical crises, especially a potential conflict with the United States. In turn, Washington faces the challenge of securing its own agricultural systems while countering China’s growing influence in the Western Hemisphere.

Introduction

China's drive to secure enough food for its 1.4 billion inhabitants has become a distinctive feature of its national strategy under President Xi Jinping. In recent years, Beijing has increasingly looked abroad, particularly to resource-rich Latin America, to strengthen its food supply in the face of rising consumption, limitations on domestic production, and geopolitical uncertainties. Latin American countries such as Brazil and Argentina have become crucial agricultural partners, supplying China with soy, meat, corn, and other staples in unprecedented volumes. These alliances are not just transforming global trade flows; they are also viewed through a national security lens. Chinese leaders often invoke the adage that the nation's "bowl of rice" must remain firmly in Chinese hands, emphasizing that food security is a strategic issue linked to sovereignty and survival.

The authors examine how China is bolstering its food security by leveraging Latin America as a breadbasket abroad, the implications for China’s broader objectives (including preparation for potential war or geopolitical disruption), and whether Beijing's measures pose challenges for U.S. food security. This document also analyzes U.S. political responses to China’s agricultural proposals in the Western Hemisphere and within its own territory.

China's Food Security Strategy: Historical Context and Recent Developments

Feeding the world's most populous country has long been central to Chinese policymaking. As early as 1996, Beijing set a target for 95% self-sufficiency in cereals in a white paper on food security. The importance of food self-sufficiency has only grown under Xi's presidency. Between 2013 and 2024, Xi mentioned "food security" in over 450 speeches and meetings, a frequency reflecting intense concern. This urgency arises from three interrelated challenges: rising food demand, constraints on domestic production, and reliance on foreign imports (Zhang and Donnellon-May, 2023).

China’s rapid economic growth and increasing incomes have driven a dietary shift toward meat and dairy products, multiplying the need for animal feed such as soy. However, China’s agricultural land is limited and is under pressure from urbanization, pollution, and erosion. Arable land has decreased by more than 12 million hectares since 2009, and water scarcity further complicates agricultural production (FAO, 2022). These factors prompted China to become a net food importer in 2004 and, by 2021, the world’s largest food importer. In 2023, China spent approximately $215 billion on food imports (Mei, 2025).

Chinese leaders increasingly view this dependence on imports as a strategic vulnerability. Xi has warned that if China cannot secure its own food supplies, "we will be controlled by others," implicitly linking food security with national security (Xi, 2021). In response, Beijing has implemented a multifaceted food security strategy, which includes the Food Security Law of 2024, mandating self-sufficiency in cereals and penalizing the conversion of agricultural land (Reuters, 2025). Authorities have even reversed reforestation efforts and converted urban parks into farmland.

The government’s "rural administrators" (農管) squads have uprooted high-value commercial crops, such as peppers and fruit trees, to ensure that staple grains are cultivated everywhere, evoking campaigns from the Mao era. In a throwback to the Cultural Revolution, even university graduates are being sent to rural areas to work the land.

Beijing is also stockpiling vast reserves. In 2023, China held over half of the world's corn and wheat reserves and increased its grain hoarding budget to $18.1 billion (FAO, 2022). Analysts believe these measures indicate not only food self-sufficiency but also preparation for war. As Chang (2025) notes, Xi's obsessive quest for food security reflects preparations for a prolonged geopolitical conflict, including a potential war with the United States.

Despite these efforts, China’s overall food self-sufficiency has decreased from 94% in 2000 to approximately 66% in 2020 (Zhang and Donnellon-May, 2023). Chinese officials have acknowledged that total autarky is not feasible and instead resort to a diversified import strategy to meet needs, especially for feed grains and proteins.

China's Investments and Agricultural Alliances in Latin America

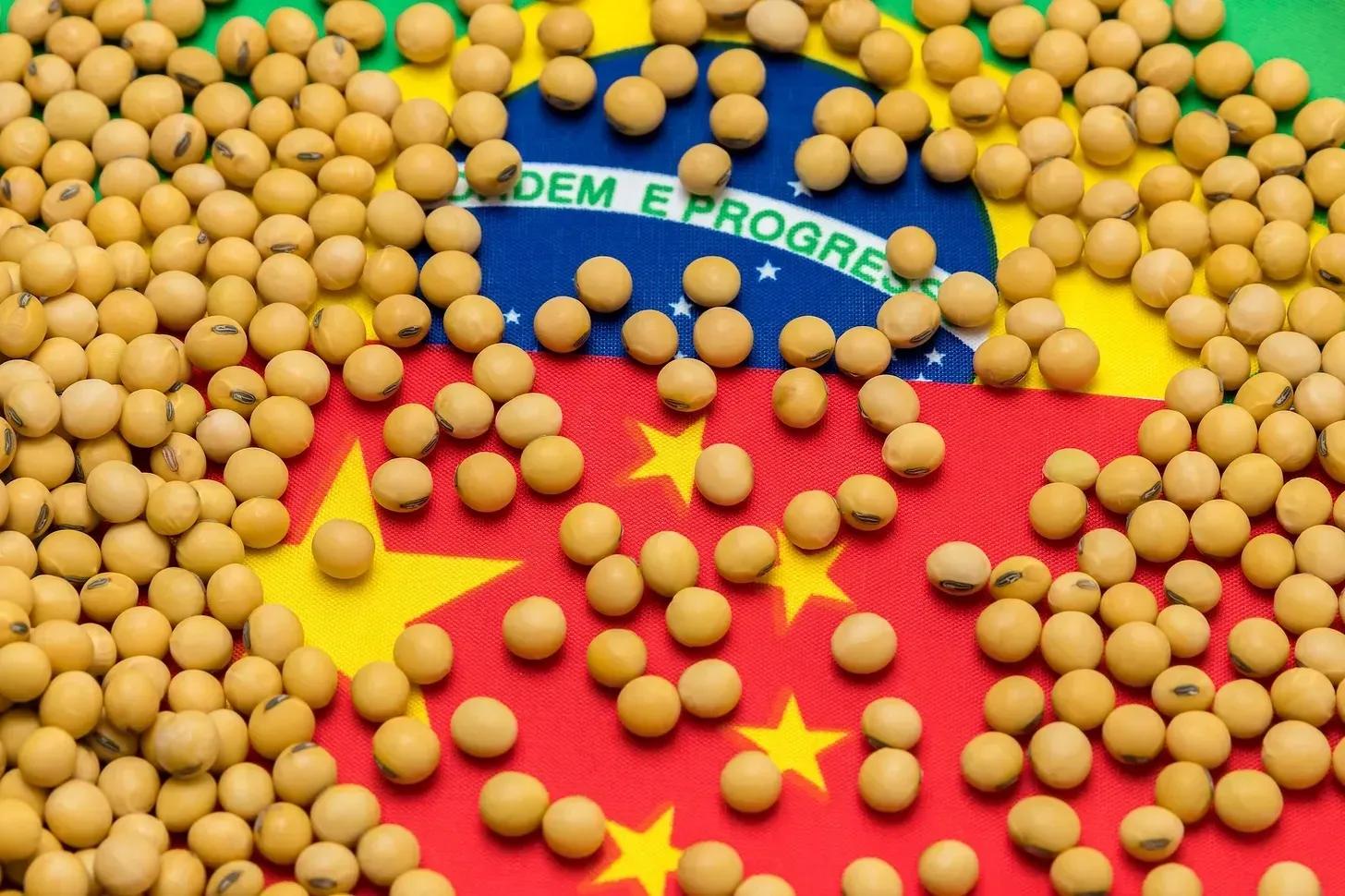

Latin America has become an indispensable source of food for China abroad, surpassed only by the United States, and in some respects, even exceeding it. In 2023, Brazil alone accounted for approximately a quarter of China’s agricultural imports (Andrés Bello Foundation, 2025).

The foundation of these links is soy, a fundamental input for animal feed. Brazil, now the world’s leading soy exporter, sends more than 70% of its soy exports to China. In 2023, China imported 88 million tons of soy from Brazil (Mei, 2025). Brazil and Argentina together now typically supply more than 90% of China’s soy imports, along with a significant share of corn and beef.

Chinese companies are not merely passive buyers but are investing heavily in agricultural infrastructure. COFCO, China’s state grain trader, operates export terminals at the Port of Santos and co-finances railroads and logistics corridors connecting Brazil’s soy belt with the Atlantic coast (Reuters, 2025; Raszewski and Garrison, 2018).

China has deliberately avoided overt land appropriation in Latin America, preferring long-term contracts and co-investments that ensure a steady supply without generating negative political reactions. This approach grants Beijing control without ownership, a geoeconomic tactic increasingly common.

Sourcing in Latin America and China’s Broader Food Security Objectives

Latin America allows China to import land and water indirectly by outsourcing the cultivation of feed-intensive crops. This supports Beijing’s internal environmental goals while satisfying consumer demand. President Xi has urged the establishment of a diversified food supply system, with foreign sources playing a central role (Xi, 2021).

The trade war between the United States and China accelerated China’s pivot to Latin America. Tariffs imposed on U.S. agricultural products in retaliation for U.S. tariffs under the first Trump administration prompted China to deepen its agricultural ties with Brazil and Argentina (Mei, 2025).

Chinese planners also consider contingencies in times of war. Latin America’s relative neutrality and its geographical distance from potential conflict zones make it a safer long-term supplier. Meanwhile, port investments, such as the Peruvian port of Chancay, food hoarding, and logistical redundancies (including floating fish farms) highlight China's contingency planning (U.S. State Department, 2022).

Impacts on Food Security and U.S. Strategic Interests

China’s incursion into Latin American agriculture has disrupted U.S. export markets. During the first trade war, U.S. farmers, especially in the Midwest, lost billions in export income due to Chinese tariffs as retaliation (Mei, 2025).

Beyond the economy, China’s growing influence in logistics and supply chains in Latin America raises long-term strategic concerns. Chinese state-owned enterprises now operate at key agricultural choke points in the Western Hemisphere. The erosion of U.S. economic leadership in the region could translate into significant geopolitical costs.

Washington also fears espionage and sabotage against U.S. agriculture. The FBI and the Department of Justice have prosecuted multiple cases involving Chinese nationals accused of stealing U.S. seed technology and smuggling plant pathogens (U.S. Department of Justice, 2023; Bureau of Industry and Security, 2022). As agriculture is now considered critical infrastructure, these threats are being taken more seriously.

U.S. Responses and Counter-Political Strategies

The U.S. response has been multifaceted:

1. Land and investment restrictions: States like Arkansas and North Dakota have enacted laws prohibiting Chinese ownership of agricultural land near military facilities (Karnowski, 2023; Suominen and Richardson, 2025).

2. Biosecurity and intelligence measures: The FBI and USDA collaborate on counterintelligence programs to combat agricultural espionage.

3. Maintaining competitiveness: Through agencies like the Development Finance Corporation, the U.S. funds sustainable agriculture projects in Latin America.

4. International coordination: The U.S. supports transparency in international grain hoarding and climate-resilient agriculture to reduce global market volatility.

Chinese Purchases of U.S. Agricultural Land: Scope, Repercussions, and Implications for National Security

While China’s agricultural strategy in Latin America has avoided land acquisition, the situation in the United States has been markedly different. In 2021, Chinese entities owned approximately 153,000 acres of U.S. farmland, a figure that, while small, raised widespread concern due to its proximity to military and strategic infrastructure (Malmgren and Schlesinger, 2025).

A turning point occurred in 2022 with the controversy over the Fufeng Group's corn mill project in North Dakota, just 19 miles from Grand Forks Air Force Base. The U.S. Air Force warned that the project posed a significant threat to national security, leading local authorities to cancel it (Karnowski, 2023).

States like Arkansas have forced the divestment of Chinese-owned farmland, such as land owned by Syngenta near sensitive areas. By mid-2025, more than 30 U.S. states had passed laws restricting or prohibiting foreign ownership of agricultural land, often specifically targeting Chinese entities (Suominen and Richardson, 2025).

At the federal level, both the Biden and Trump administrations expanded CFIUS oversight to block agricultural land purchases near critical infrastructure. The 2024 NDAA codified these reviews, and a July 2025 executive order added the integrity of the food system as a factor in national security assessments (Suominen and Richardson, 2025).

Critics warn that Chinese entities could circumvent restrictions through shell companies or intermediaries. Others argue that even limited ownership of land could be used for surveillance, biological disruption, or strategic influence. In the context of worsening U.S.-China rivalry, U.S. farmland is now viewed as a potential vulnerability.

Conclusion

China’s strengthening of food security through alliances with Latin America—and selective acquisition of U.S. agricultural land—represents a crucial element of its national resilience strategy. These measures serve economic, strategic, and political purposes, especially as Beijing anticipates the risk of global conflict or trade disruption.

For the United States, the implications are profound. China’s agricultural diplomacy threatens U.S. export markets, undermines its traditional influence in Latin America, and raises national security concerns over land ownership and biotechnological espionage. Washington must act strategically, balancing internal defensive measures with proactive engagement abroad.

Ultimately, food security is no longer just an economic issue; it has become a key frontier in the competition between great powers in the 21st century.

References

Chang,G. G. (August 2, 2025). Xi Jinping indicates that China is preparing for a major attack. The Daily Caller. https://dailycaller.com

United States Department of State (2022). Food security strategies in the Western Hemisphere (Circular Report No. 17). Washington, D.C.

U.S. Department of Justice (2023). Two scientists from the People's Republic of China charged with agricultural smuggling [Press Release]. https://justice.gov

Inter-American Dialogue. (2018). China's agricultural investment in Latin America. The Dialogue.

Andrés Bello Foundation. (2025, July 1). Argentina begins soybean meal exports to China.

Karnowski, S. (February 2, 2023). The Air Force opposes a Chinese company's corn plant in North Dakota. Air Force Times. https://apnews.com

Malmgren, H., and Schlesinger, S. (2025). How much U.S. land do China and other countries really own? Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

Mei, M. C. (March 4, 2025). How China reduced its dependence on U.S. agricultural imports and refined its tools for the trade war. Reuters. https://reuters.com

Bureau of Industry and Security, U.S. Department of Commerce (2022). Report on the illicit export of seeds and U.S. agriculture. Washington, D.C.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (2022). Food Balance Sheets – China. FAOStat database. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/

Raszewski, E., and Garrison, C. (November 29, 2018). Argentina and China sign a multimillion-dollar deal to renovate a cargo railway. Reuters. https://reuters.com

Reuters. (June 3, 2025). China increases its stake in Brazilian ports to reduce dependency on U.S. food imports. OFI Magazine.

Suominen, K., and Richardson, A. (July 8, 2025). The U.S. will prohibit the purchase of farmland by China, citing national security reasons. The Washington Post. https://washingtonpost.com

Xi, J. (March 2021). Speech at the CCPCC meeting on food security. Xinhua News.

Zhang, G., and Donnellon-May, G. (2023). What do we really know about China’s food security? The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com

José Adán Gutiérrez is a Senior Fellow at Miami Strategic Intelligence Institute, whose founder, President, and Chief Economist is the co-author of this note, Dr. Rafael Marrero.

Comments