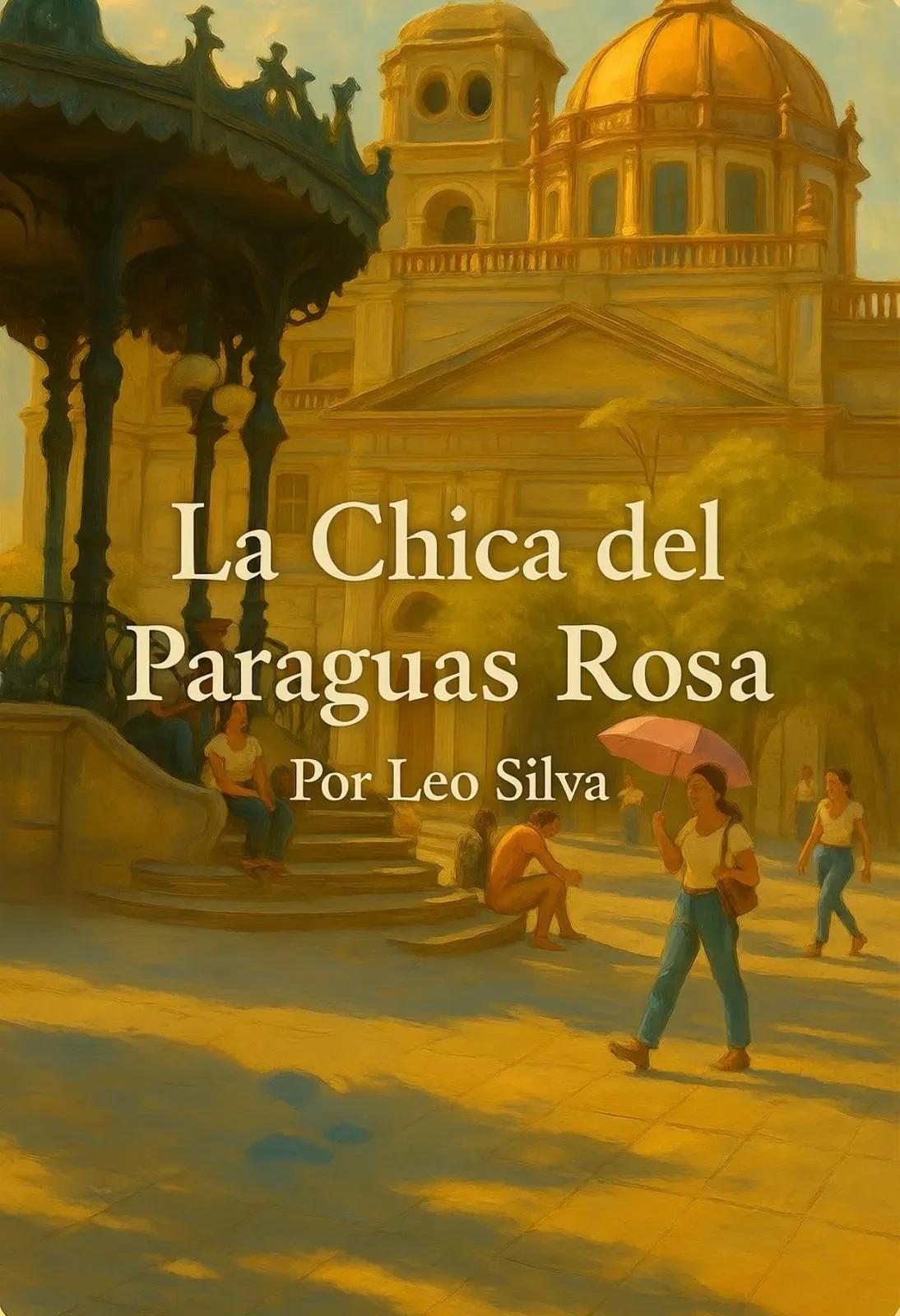

She crossed the plaza under a grey, overcast sky, the pink umbrella above her head shining like a lantern in the twilight. Its color seemed too tender for that place: a childish hue against the stone of a cathedral that had swallowed centuries of sorrow. She walked briskly, as if heading to class or work, with the silent conviction that tomorrow belonged to her. She could not know that the stones beneath her feet had drunk blood, nor that the air above her head had once erupted with gunfire. She carried only hope with her, and at that moment, it was enough.

From afar, she could have been any young woman —on her way to school, work, or to meet a friend. Her umbrella shielded her from a drizzle so light it barely touched the ground, more a symbol than a refuge, as if she were carrying the sky itself in a gesture of defiance. She moved with the unconscious confidence of youth, with intact dreams and faith in the future. For her, the plaza was nothing more than stone and pigeons, vendors offering fruit with their voices over the constant murmur of life.

But for others, for those who remembered, the plaza was something more. Beneath the altar of the cathedral she crossed lies the body of Cardinal Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo, gunned down at Guadalajara airport in 1993, when the Arellano Félix brothers mistook his car for that of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. His death, brutal and senseless, was not just a tragedy of faith but an open wound in the heart of Mexico. His crypt remains there, illuminated by candles, silent, reminding that even men of God were not spared from the crossfire of the narco war.

Forty years earlier, not far from where her umbrella flourished against the grey sky, DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena was kidnapped in broad daylight, his fate sealed in the shadows that dominated these streets. His memory fades slowly into eternity, but for those of us who serve, his name is not history: it's a scar, a wound that reignites every time we recall the price of silence and impunity. Caro Quintero and Fonseca Carrillo, names engraved both in files and in the city's conscience, walked these same streets with an arrogance that seemed to say Guadalajara belonged to them. Their shadows spread through plazas, markets, and churches, until time erased them in whispers.

The girl with the pink umbrella knew nothing of this. She walked intact, without ghosts, with steps as light as the pigeons she lifted around her. The city remembered, but she did not. And perhaps that was a form of mercy.

As I watched her cross the plaza, I felt the weight of my own memories pressing on my chest. I thought that innocence is always temporary. We carry it like a fragile shield until the world breaks it with the brutal force of reality. I remembered my own youth, now distant, when I too carried dreams yet untested. I recalled the first time I stood over a body, the way violence leaves marks not only on the dead but also on the living who witness it. The girl’s umbrella seemed less a protection against the rain than a prayer: a bright color raised against the grey, hope walking among shadows.

Guadalajara is not unique in this. Every city has its ghosts, its corners stained with blood, its silences that scream louder than words. The plazas of Medellín, where laughter once echoed over fear-soaked cobblestones. The streets of Matamoros, where families took refuge while bullets stitched the night. Even the neighborhoods of my own country, where violence wears other faces but leaves the same scars. There is always an umbrella, a ribbon, a child’s laughter: something fragile and luminous that insists on surviving.

The girl with the pink umbrella is more than a passerby. She is metaphor, symbol, reminder. She represents all those who walk forward without knowing, carrying their innocence through landscapes that have seen too much blood. She teaches us that hope is not erased by history; it only hides, waiting for the young to lift it up again.

Even so, I cannot shake the tension between her innocence and what lies beneath her feet. That tension defines places like Guadalajara, where beauty and violence share the same space. The cathedral rises with grandeur, its domes shining in the sun, while its crypt holds a murdered cardinal. The vendors arrange fruit in pyramids of color, while the nearby walls hide bullet holes under layers of fresh paint. Life insists on continuing, as if the challenge is also a form of prayer.

I wonder if innocence is not also a form of defiance, not just ignorance. Perhaps the girl with the pink umbrella knows nothing of Posadas Ocampo, of Camarena, of Caro Quintero, or Fonseca Carrillo. But even if she did know, even if she understood the ghosts pressing against the walls of the cathedral, she might still keep walking, the umbrella tilted, believing in tomorrow. And perhaps that, more than anything, is what redeems us.

Because innocence, as ephemeral as it is, has the power to soften the edges of memory. For a moment, the plaza belongs not to violence or ghosts but to the sound of hurried steps on the wet stone, to the pink flash against the grey, to the promise of tomorrow carried by someone too young to remember yesterday. In that moment, history bends —it is not erased, nor forgiven, but momentarily softened under the audacity of hope.

I also think of the red ribbon, of the laughter of another girl that resonated over the same stones, scaring pigeons into the sky. I think of how, on the other side of the border, Camarena's legacy is remembered every October during Red Ribbon Week, when children pin a scarlet ribbon on their shirts as a promise against drugs. The ribbon in America, the umbrella in Guadalajara: both fragile emblems raised against the storm of history. Ribbon and umbrella, laughter and haste: two small banners of innocence defying the weight of memory.

I carry memory in another way. I know the names, the stories, the bodies that were left behind. I know the silence that follows violence, heavy and persistent. And yet, seeing these girls, I feel something stir within me —something akin to gratitude, something close to grief. Gratitude that innocence still dares to walk these streets. Grief because I know it will not last forever.

Perhaps that is the mercy of the young: to laugh where the dead still whisper, to walk beneath a pink umbrella as if tomorrow were already promised. And perhaps that is how hope survives —not in the memory of those of us who bear the scars, but in the dreams of those who have yet to be broken.

Leo Silva is a former special agent of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) of the United States, with years of experience working and living in Mexico. Throughout his career, he witnessed the complex social, cultural, and human realities that coexist beneath the surface of violence and power. Today, he writes narrative essays and reflective chronicles that explore memory, identity, and the contradictions of contemporary Mexico. His work seeks to preserve the human stories that seldom appear in headlines.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

This text was born out of an image. A friend sent me a promotional photograph of my book El Reinado del Terror, taken in Guadalajara, right in front of the steps of the cathedral. In the image, the book appeared in the foreground; behind, almost unnoticed, a young woman crossed the plaza with a pink umbrella.

What stopped me was not the photograph itself, but the contrast. The girl moved naturally, unaware of the historical weight of the place, not knowing that these same stones had witnessed episodes of violence that deeply marked the city decades ago. Her Innocence, so visible, so everyday, seemed to defy the dark memory I carried with me.

That tension between what is remembered and what is ignored, between memory and hope, was the impulse that led me to write this essay.

Comments