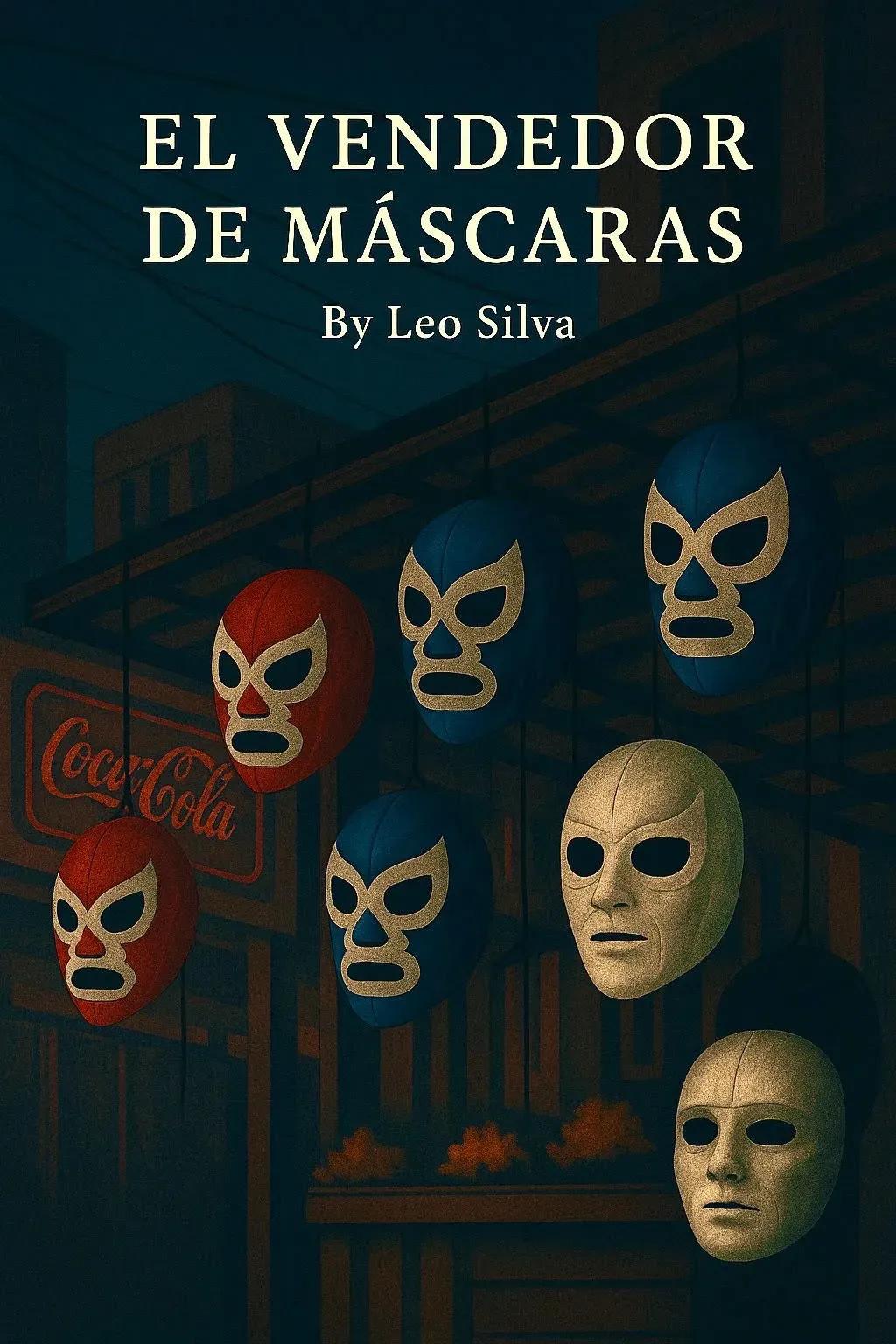

He sold masks on a busy corner in downtown Monterrey, under a tangle of electrical wires and a faded Coca-Cola sign that hadn't been lit for years. His stand was a small explosion of color in a city that often dressed in gray: rows of red, blue, and silver lucha libre masks fluttered in the wind like strange tropical birds.

From a nearby speaker, Linda Ronstadt's voice and Blue Bayou floated over the afternoon air, slow, tender, nostalgic. The mask seller hummed softly while sewing one, the melody almost lost amidst the noise of traffic. The song spoke of peace, of home, of simpler times—things that in Monterrey already seemed impossible.

He designed the masks himself, he once told me. He cut them, sewed them, and painted them by hand.

Each mask was a character, a dream, a way for a child to feel like a hero. Tourists stopped to take photos; locals bought them for birthdays. I had seen diplomats, marines, and even high-ranking officials from Washington take one home for their children.

They always left smiling.

He smiled too, a smile that mixed pride and weariness.

One afternoon I asked him how business was going. He hesitated, looked over my shoulder, and lowered his voice.

—They’re asking for money —he said—. A percentage. Every week. The Zetas.

He looked at his hands, rough from years of work.

—What do I do, sir? If I don’t pay, they’ll kill me. If I pay, I can’t feed my family.

There wasn’t much I could say. Monterrey was bleeding then, and no one was safe from the slow poison of fear that consumed the city. I told him to be careful. He nodded, smiled again, and handed me a mask, silver and shiny, like a newly minted coin.

That was the last time I saw him.

The following week, his corner was empty. The hooks were still hanging from the wooden frame of the stand, swaying slightly in the wind. No police tape. No notice. Just silence.

Someone said he had left town. Another, that the Zetas had taken him away. But in Monterrey, rumors were as common as dust, and just as easy to choke on.

For us, the disappearance of the mask seller was an early sign of the chaos to come, a portent that few perceived and even fewer understood. His absence should have been a red flag, but the city was already too numb, too busy surviving to notice.

Two weeks after his disappearance, the Zetas attacked the U.S. Consulate and then methodically chased down and murdered nine soldiers. Fear settled over the city like dust. The streets emptied early. Conversations grew shorter. Tension was a living being, as thick as the smog hanging over the mountains.

We were busy with the El Canicón operation, and in the midst of that chaos, we forgot about the mask seller, until one afternoon I passed his old stand and realized he was gone forever. The hooks were still there, swaying in the wind.

Inquiries among other vendors and nearby businesses led to nothing. He had simply vanished.

The reign of terror of the Zetas spared no one. Multi-million dollar corporations, teachers, even street vendors: all lived under the same dark canopy of fear. The richest families in Monterrey fled north, seeking refuge behind the gates of San Antonio, the high walls of Houston, the artificial tranquility of the suburbs of Dallas. But men like the mask seller had nowhere to flee. They sought escape in silence, in prayer, in the sweet mercy of disappearance.

Sometimes I still imagine his masks dancing in the air, each carrying the face of a man who just wanted to make a living, who believed that color and courage could survive in a city at war with its own shadows.

I still keep one of his masks: silver, soft, hand-sewn. Sometimes I take it out and wonder what stories his hands carried the day he made it. It is no longer just fabric. It is the memory of a man who believed that, even in a city dominated by fear, beauty was worth the risk.

Every thread in that mask is a reminder: we all wear one to survive.

His disappearance drove me to do my job better. Monterrey had been a beautiful city, and the Zetas were ruining it for everyone, so much so that even a street vendor couldn't make an honest living. It was frustrating. Infuriating. His death—or whatever happened to him—became a silent promise I made to myself: that men like him deserved better, that this city deserved better.

I retired long ago, from my job and from Monterrey, but every time Blue Bayou plays on my playlist, I see him again under that faded Coca-Cola sign, sewing hope into a silver mask. That voice, that yearning for a place untouched by violence. Monterrey was once that place. Maybe that's why the song still hurts: because, as Linda sang, we all want to return to a safe place, to a place that no longer exists.

Leo Silva is a former Special Agent of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) of the United States who served in dangerous Mexico.

Author's Note

I met the mask seller during one of the darkest periods in Monterrey's history. His small stand on the corner stood out for its color, for its joy: a challenge to death in a city drowning in fear. For me, his absence became a silent reminder of why I did my job and why telling these stories remains important. Because behind every headline and every statistic, there is a name, a face, and a life that deserved better.

Comments