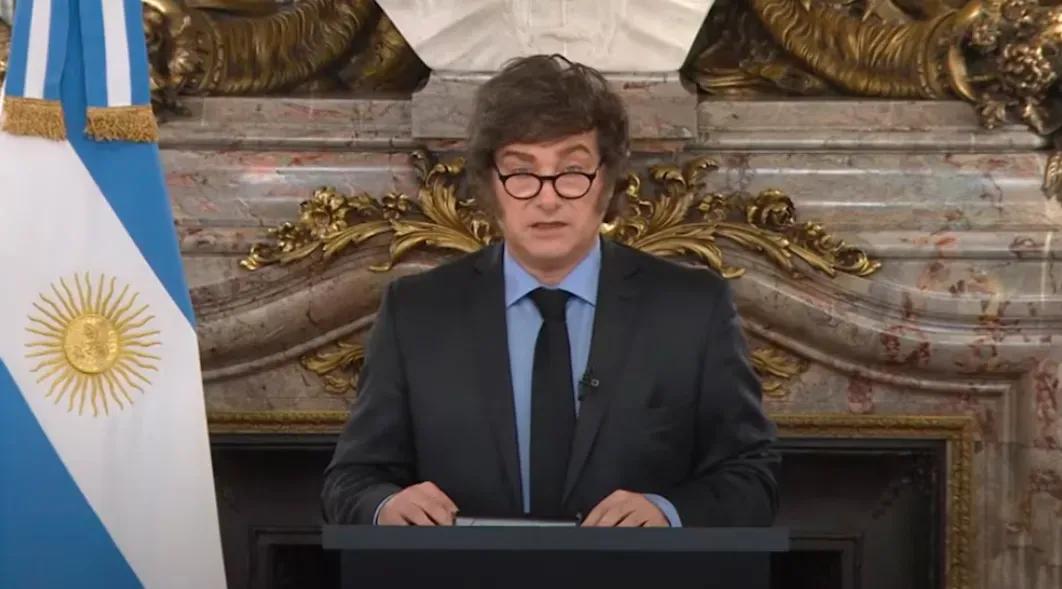

The politics have their ironies: Rome wasn’t built in a day, but it could very well catch fire before consolidating. In the most recent national broadcast, Javier Milei exhibited a different register: sober, contained, even solemn. For the first time, we saw a president without verbal outbursts, without trench-shouting, without the ritual of closing his speech with that “Long live freedom, damn it!” that so often served as a rallying cry, but which in the exercise of power became a performative gesture. Last night, however, a serious, almost institutional Milei emerged, acknowledging that the sacrifices demanded of society did not reach the most vulnerable and that attacking retirees, disabled individuals, the healthcare system, and universities does not constitute a viable or legitimate path.

This discursive shift, although merely rhetorical, is not minor. The president, who until recently cultivated the epic of the “anti-system,” now presented himself as a statesman who listens. He acknowledged mistakes, hinted at the need for corrections, and at least on the surface, accepted the evidence that a government eroding basic rights runs the risk of becoming its own executioner. Argentine politics, with its history of pendulum cycles and leaders who devour themselves, knows that speeches are not enough; however, the change in tone marks a gesture that can be interpreted as maturation or as mere survival strategy.

The change in tone was not only rhetorical: it was accompanied by concrete announcements aimed at conveying a message of social sensitivity. The president stated that “the toughest years we faced were the first ones, and therefore we can affirm… that despite the circumstantial turbulence, the worst is behind us.” That phrase aims to install the idea of a turning point: the most painful phase would be in the past.

The numbers reinforced that narrative. For 2026, Milei announced real increases above projected inflation in traditionally hard-hit areas: retirements (+5%), health (+17%), education (+8%), and disability pensions (+5%). In the same vein, 4.8 trillion pesos will be allocated to national universities, implicitly recognizing the strikes and grievances that resulted from cuts in the academic and student community.

He also admitted the gap between the official discourse and the daily lives of millions: “many still do not perceive it in their material reality.” This recognition, although partial, signifies a break from the narrative of denial and confirms that social and political pressure has left a mark.

The underlying question is whether this sober Milei responds to a genuine conviction or to the need to decompress after weeks in which allegations of alleged corruption —even involving his inner circle— and management scandals set off alarms. The narrative of the president as the “uncorruptible outsider” erodes when the shadow of kickbacks touches his sister, a key figure in his political assembly. In that sense, the change in register can be read as a defensive reaction: an attempt to shield the presidential figure amid wear and tear.

Milei defined fiscal balance as the “cornerstone of our government.” What is non-negotiable is austerity: if revenues fall or expenses exceed what is planned, he warned, allocations will be adjusted to maintain that balance. In practical terms, that premise can guarantee coherence and discipline, but it also implies that any external shock —an increase in international prices, a drop in exports, a wave of social demands— can trigger new cuts in the most sensitive sectors.

In comparative perspective, Milei’s situation resembles global experiences where leaders who arrived with a rupture discourse —from Bolsonaro in Brazil to Tsipras in Greece— had to mutate toward institutional pragmatism when the costs of radicalism became unbearable. This transition reveals a paradox: populist leaderships, which are legitimized through confrontation, often need the guise of moderation to survive in power. But that moderation, when perceived as forced, can be seen as capitulation, thereby losing the base that brought them to government.

The announced budget, with increases in sensitive areas, aims to show social sensitivity. However, it remains to be seen whether those allocations will withstand inflation and whether they will translate into concrete improvements for retirees, students, and patients in the public healthcare system. Argentine history teaches that numbers are fragile when economic reality imposes itself. The risk is that this discourse falls into what Max Weber called “the ethics of intentions” rather than “the ethics of responsibility”: good words without practical efficacy.

Perhaps the deeper question raised by this moment is not only whether Milei listened to the people but whether he is willing to reconsider who conducts Argentine politics and with whom he chooses to surround himself. In contexts of high conflict, the government team can be both a lifeline and a lethal burden. The concentration of power in the hands of relatives, the lack of experienced management personnel, and international isolation limit the Executive’s capacity to maintain solid governance.

In an interdependent world, where geopolitics pressures from multiple fronts —the tension in Ukraine, the pulse between the United States and China, the European migration crisis— Argentina cannot afford a government that is perceived as erratic, trapped in internal disputes or in grandiloquent discourses without material correlation. The political capital that Milei still retains will quickly dissipate if it does not translate into verifiable results.

Last night’s speech can be interpreted as a turning point: the beginning of a more serious, less violent management with a sense of institutionalism. But it can also be a simple artifice, a script read out of obligation in the face of social and political pressure. Argentine history is rife with leaders who promised corrections and ended up consumed by the flames of their own contradictions.

The essential question remains open: are we witnessing the birth of a Milei statesman or the umpteenth chapter of a leadership that improvises according to the circumstances? Rome wasn’t built in a day, but Argentina also does not have time to catch fire again.

Comments