There are nights in Monterrey when the city feels softer, as if the mountains themselves had exhaled. The heat rises from the slopes, the air cools enough to invite stories, and the sky over San Pedro takes on the color of deep ink, with Chipinque outlined like a dark, familiar altar.

My friend liked to organize gatherings on nights like these.

His patio faced the mountain: stone floor, a rustic wooden table, and a grill that seemed to have lived as long as any of us. A trusted cook—one of those men who learned by observing parents and grandparents—arrived in the afternoon to prepare the borrego a la griega as it should be: a whole lamb, slowly roasted over mesquite coals, suspended and turned with patience, while the smoke spread through the neighborhood announcing that something worthy of remembrance was about to happen.

By the time the guests arrived, the ritual was already alive.

Plates of jalapeños stuffed with cream cheese and wrapped in bacon passed hand to hand. Casseroles of frijoles charros, still steaming, were placed on the table to whet the appetite. In the center, a heavy molcajete overflowed with guacamole: mashed avocado with onion, cilantro, and lime. Then, the cook grated fresh mozzarella cheese directly on top, letting it melt like a secret that only that house understood.

Bottles of beer sweated in the cool air.

Tequila passed from hand to hand, never empty.

Cuban cigars burned at the tip, their smoke rising before disappearing into the midnight blue sky.

The Chipinque watched us silently, its peaks bathed in silver by the autumn moon.

We ate until the conversation softened and the lamb was reduced to bones. People laughed, debated, shared stories that only made sense after a few drinks.

Eventually, guests with small children or early commitments said their goodbyes, leaving a smaller group: those of us who never rushed to end a good evening.

Someone poured a final round of tequila. Another switched to cognac, as if changing rhythm. Sometimes we set both aside to prepare carajillos—espresso mixed with Licor 43—the drink with which my friend taught me to close the nights in Monterrey, when the body was full and conversation had just begun.

The fire had reduced to embers, glowing softly, giving just enough heat to make us lean forward.

It was then that my friend leaned back in his chair, looked towards Chipinque, then back at the house, and said:

—I’m going to tell you the story that made my father who he is.

I followed his gaze to the sliding glass door.

Through it, we saw his father slowly moving through the living room. Ninety years old and still with a demeanor that made one think the world learned to walk slower around him. His back hunched, shoulders bowed by time, but something remained intact: the silent authority of a man who had spent his life facing chaos with steady hands.

He walked with small, careful steps, a cup of tea trembling between his fingers.

There was a softness in my friend’s face as he watched him, a mix of pride, tenderness, and a quiet sadness for the years his father no longer had. —Most people know him as a good doctor —he said quietly—. But they don’t know why.

He took a slow sip of tequila, set the glass down carefully, and let the silence envelop us before he began.

—It was before Monterrey. Before I was even an idea. He was in the United States, doing his residency at Scott and White, in Temple, Texas. Young. Always tired. Living on hospital coffee and adrenaline.

A slight smile crossed his face, as if he could clearly see the man his father had been. —He had the night shift —he continued—. Night after night in the emergency room. He hated it, not because of the work, but because it made him feel invisible. No one important arrives at three in the morning. They sent him what others didn’t want to deal with.

He looked towards the moon, as if measuring time against it. —One winter night, just before midnight, the ambulance doors swung open, and they came pushing in a man who looked like he had been dragged from a ditch.

He didn’t rush the description. —He was so beaten that, according to my father, he hardly looked human. His face swollen and purple, one eye nearly closed. Dried blood in dark lines running down his forehead. His shirt stiff with dried vomit. His pants soaked in urine. Bile on his neck. And the smell… oh my God, the smell arrived before the man.

He shook his head. —A nurse had to take a step back and cover her mouth. She couldn’t stand it.

The man clung to consciousness with what little he had left, coming in and out.

He murmured sounds that might once have been words, now destroyed by alcohol and a concussion.

—No identification. No wallet. Nothing —my friend said—. Someone had beaten him,

robbed him, and thrown him away. Just a broken body that, luckily, made it to the hospital and not to the morgue. That’s how they saw it.

He took another sip. —And as soon as they put him on the stretcher —he continued—, all the senior doctors vanished. They didn’t even pretend they were going to help.

His eyes narrowed slightly. —One said it aloud: “Leave him for the resident. I’m not touching that tonight.” And just like that. They left. They left him there.

For a moment we only heard the distant murmur of the neighborhood and the sound of the cook washing dishes inside the house. —But my dad —my friend said— never turned his back on anyone.

The young resident put on new gloves and stepped up. He did what no one else wanted to do. He leaned over the man, inhaled everything that the others avoided. And instead of stepping back, he began. —Once he told me —my friend recalled—: “A patient is a patient. Even if he smells like the very hell.”

So he cleaned him. He wiped the blood from his face. He washed the vomit from his hair. He scrubbed the dirt from his skin until he could see the man beneath all that. He checked his pupils.

He took vital signs. He started stitching up the cuts on his face and arms. He talked to him the entire time, even though the man couldn’t respond anything coherent.

The hours passed slowly. Machines beeped in the darkness. Nurses came and went from other rooms. The veteran doctors never returned. —He could have done the bare minimum —my friend said—. No one was watching him. But he stayed. He watched over him. Adjusted the IV. Made sure he didn’t get worse. He treated him as if he mattered.

He looked towards the house. —That’s him —he simply said.

And then morning came.

Around seven, that strange hour when the night shift believes it has survived and the day shift has yet to take control, the emergency room doors swung open again.

This time it wasn’t another stretcher.

—It was a group —my friend said—. High-level doctors. Administrators. And behind them, men in dark suits, the type you only see when something serious is happening that no one wants to explain.

They went straight to the room.

They didn’t look at the resident.

They didn’t ask him anything. —They pushed him aside —he said—. As if he were in the way.

The young man stepped back, bewildered, feeling as if he had stumbled upon something too big.

When his shift ended, no one said a word to him. He went home exhausted, replaying the night, convinced he had made a mistake. He fell asleep with his clothes on.

Hours later, the phone wouldn’t stop ringing. —At first, he ignored it —my friend said—. But it kept ringing and ringing. When he finally answered, it was the Chief of Medicine. No greeting, no niceties: “Return to the hospital. Now.” He paused. —He was sure they were going to fire him.

They took him straight to the Chief’s office, filled with doctors, administrators, and the men in suits. They interrogated him, mostly: the arrival, the injuries, what he had said, what he had done.

Then they guided him down the hall. —The man was sitting —my friend said—. Clean. Shaven. In a gown. He looked like another person. Someone you would greet in an elevator.

The patient looked at the men in suits, then at the doctors.

And then he saw the resident at the door. His expression changed. Recognition. Gratitude. He extended his hand and pointed directly at him. —That one —he said—. That’s the only one who helped me.

The silence fell over the room. My friend let the moment breathe. —The man who attended to me —he finally said— was Sam Houston Johnson, brother of then-president Lyndon B. Johnson. He was missing. The Secret Service was searching for him all over Dallas. And the only person who treated him with dignity was a resident who had no idea who he was.

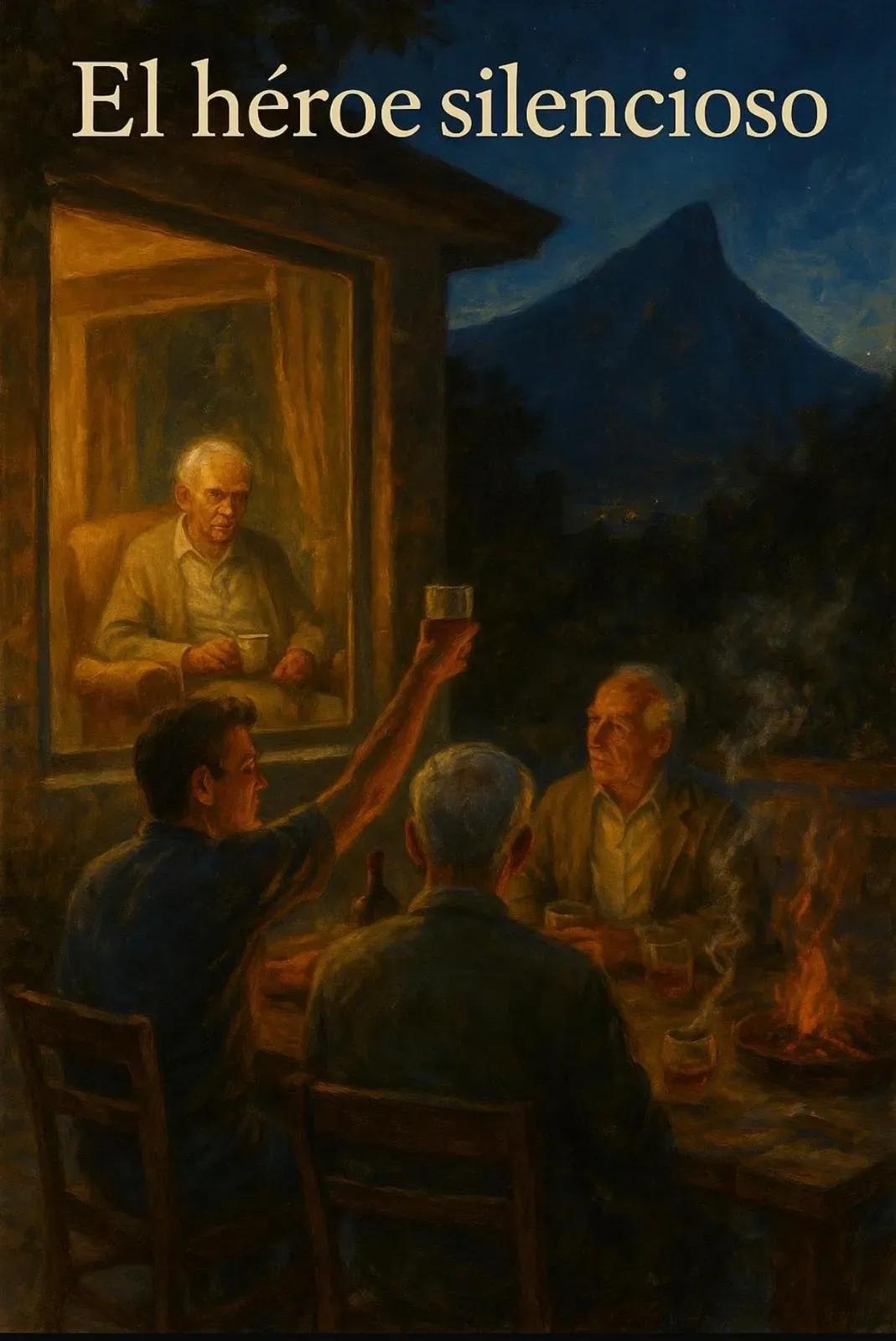

The patio fell silent. The cook had left. The embers barely glowed.

Above us, Chipinque remained still, as if it had heard that story many times before and still approved of it. —My father became a hero overnight —my friend said—. But that never mattered to him. What he remembers is the smell. The dirt. The way everyone walked away. And what he felt at four in the morning when he decided that even that man, as broken as he was, deserved for someone to stay.

Inside the house, his father sat in his armchair by the window, eyes closed, the cup of tea resting in his lap. He looked small and strong at the same time, like someone who had given the best of himself to the world and now rested in the peace that followed. —He keeps telling that story —my friend said quietly—. As if he fears the world will forget it.

I watched the old man through the glass. I imagined the decades under fluorescent lights, patching up strangers, saving lives of people who would never know his name.

I thought of the man who entered without an identity and left being someone important.

And then I understood: it wasn’t a story about power.

It was a story of decency. Of honoring the humanity of someone long before knowing whether the world believed they deserved it.

Some men change the world in silence.

Some heroes never hear applause.

And sometimes, the greatest act of mercy is to treat a stranger—no matter how broken they arrive—as if their life still had value.

My friend raised his glass towards the house. —To him —he said.

We raised ours too: towards the old man inside the house, towards the mountain above us, towards the memory of a night shift many years ago. We toasted to a story that could have been lost, if not for a son who refused to let it die.

Author’s note

Most of my writings explore territories where power, violence, and drug trafficking shape extreme human decisions. This one doesn’t.

The silent hero is not a story about crime or politics. It’s a story about character.

This text exists to remind us that true integrity does not depend on the status of the person in front of us, but on our willingness to treat them with dignity even when we don’t know who they are.

Leo Silva is a former agent of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), whose main destination was the tumultuous Mexico of the Zetas and drug cartels. Today, retired, he rescues through his essays true anonymous heroes who during their years of service put humanity into a violent and heartbreaking scenario.

Comments