Does international law matter today when it was systematically ignored for years regarding Venezuela?

Does it matter now, when the accusations have been constant, when reports have piled up, when the atrocities have been documented and yet the international system chose to look the other way?

For more than a decade, Venezuela has lived under a regime that annulled basic freedoms, persecuted opponents, imprisoned political leaders, used torture as a method of discipline, and pushed millions into exile. None of this was secret. Nothing occurred in darkness. There were reports from the UN, from the OAS, from international human rights organizations. There were testimonies, names, dates, victims. And yet, actual condemnations were scarce, late, and often lukewarm.

The UN did not work. Or worse, it looked the other way.

The majority of states did not firmly condemn it.

Multilateral bodies issued lukewarm statements while the day-to-day life of millions of Venezuelans became directly inhuman.

Why now?

Why do the defenders of legality, sovereignty, and international order appear now?

Where was international law when fraud was committed in the elections?

Where was it when there were political prisoners?

Where was it when censorship prevented even seeing news on television?

Where was it when torture became a daily occurrence for thousands of Venezuelans?

The UN exists, yes. International law exists, too. But its ability to respond to Nicolás Maduro's regime has been, at best, insufficient. Due to a lack of political will. Many states preferred comfortable neutrality, strategic silence, or ideological relativism rather than a clear and sustained condemnation.

When Maduro falls, the debate seems to abruptly shift to the legality of the procedure, the risks, the precedents, and, almost automatically, oil.

Is that really the priority now?

Should the center of the debate really be whether the United States benefits economically, when for years no one mobilized with the same intensity for the destroyed lives?

Another dangerous phrase is also repeated: “the Venezuelans had to fend for themselves”.

How “alone”?

When they couldn't speak freely?

When protesting meant prison, exile, or death?

When they could not even stay informed because censorship was total?

This is not to deny that there are geopolitical interests. It would be naive to do so. Nor is it to stop critically observing the role of the United States from now on. That is necessary and healthy. But reducing decades of suffering to a discussion about natural resources is to dehumanize what has been lived.

Today, for millions of Venezuelans, what matters is that the man who subjected them for years is no longer in power. That a possibility of transition is opening— for the first time in a long time. Difficult, uncertain, full of risks, yes. But real.

Anaís Castro, a Venezuelan in Argentina, expressed it with a clarity that makes many uncomfortable:

“If I feel a bitter justice, because at least that dictator and murderer is taken out of my country, allow me to celebrate, allow me to be happy, because they have taken too much from us.”

“Do not contaminate our joy of feeling that a little bit of justice is being done. Don’t take it away from us.”

“I don’t know what our future is, but I know our past very well.”

That is what many do not want to hear; that there are peoples who have been deprived of so much for so long that celebrating a fall is not frivolity, it is emotional survival.

There is also a selective memory that is impossible to ignore. The Argentine dictatorship is invoked strongly and rightly as a political banner, as a symbol of “Never Again.” But when it comes to a current, living dictatorship, operating today, that commitment disappears or is relativized. It is justified, minimized, or outright denied.

Not everything is black or white, it is true. But there are lines that should not be crossed. One of them is to justify or relativize a dictatorship in the name of a supposed ideological coherence.

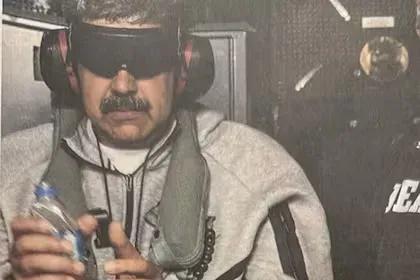

Maduro was captured.

That does not solve everything.

It does not guarantee automatic democracy.

It does not erase the suffering experienced.

But it is a central political fact. And, for many Venezuelans, deeply reparative.

Later we will discuss the role of the United States.

Later we will discuss institutional reconstruction.

Later we will discuss limits, controls, and balances.

Today, at least for today, something more basic and human is required: to understand and respect that a people who have been silenced, repressed, and humiliated for years have the right to feel that, for the first time, justice is peeking through.

And yes: to celebrate it.

Comments