When the Queensland Government, supported by the report Governance in the Age of AI: Preparedness and Responsible Leadership, was published by the Queensland Geological Survey in collaboration with FrontierSI, it entered a global debate already filled with warnings about artificial intelligence. However, the report itself is careful to dampen the technological hype. Instead, it positions AI, particularly generative AI, as a stress test for something much more fundamental: how organizations govern data, make decisions, and take responsibility for the technologies they implement.

As the authors indicate from the outset, “the critical question is whether the organization or governmental department is technically prepared to implement these services responsibly and at scale.” That approach sets the tone for the entire document. This is not a manifesto for the rapid adoption of AI, nor a call for new legislation. It is a practical governance document aimed at translating policy principles into institutional reality.

From Technical Success to a Governance Problem

The report is based more on experience than theory. It relies on a generative AI proof-of-concept known as the “Digital Librarian,” developed by the Queensland Geological Survey to enhance discovery across thousands of geological reports. By utilizing large language models and retrieval-augmented generation, the system demonstrated that AI could synthesize complex, unstructured data much more efficiently than traditional search tools.

But the success exposed a deeper issue. While the technology worked, the organization recognized that moving from proof-of-concept to a production public service raised questions that existing policies did not answer. The report notes that, although AI governance policies emphasize ethics, quality, reliability, and explainability, they “offer limited practical guidance on how to translate these principles into an implementable framework.” The document was written to fill that gap.

Preparation Before Deployment

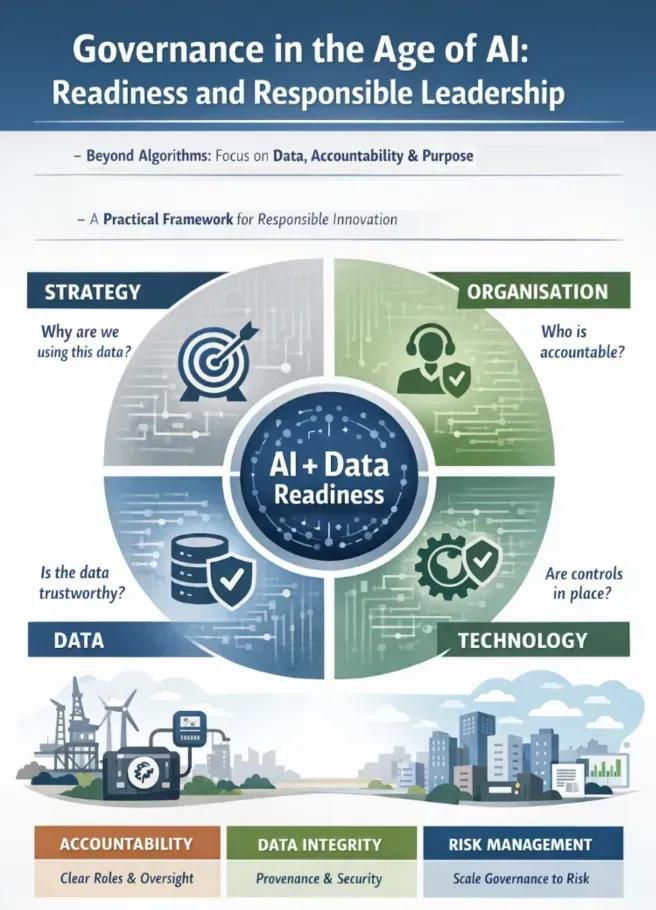

A central contribution of the report is its insistence that the adoption of AI is not primarily a technical challenge. Instead, it introduces a Readiness Assessment Framework for AI built around four domains: strategy, organization, data, and technology. These domains are deliberately interdependent. As the report explains, “effective AI adoption requires preparedness beyond technological maturity,” and data, governance, leadership, and culture must evolve together.

This approach is legally and regulatory significant. Many technology-related conflicts arise not because a system has failed, but because no one could explain who was responsible, why certain data were used, or how decisions were made. By focusing on preparedness, the report recontextualizes risk as something that accumulates when organizations scale technology faster than their governance capacity.

Governance That Scales with Risk

The report also rejects a one-size-fits-all oversight model. It proposes a tiered governance framework aligned to the lifecycle of an AI system, from planning and design to deployment and monitoring. Governance artifacts, such as accountability frameworks, risk and impact plans, privacy and security controls, and assurance mechanisms, are introduced progressively, depending on the scope and risk profile of the system.

As the authors suggest, governance should be “applied proportionally to the scale, complexity, risk profile, and lifecycle of the AI-enabled service.” This language closely resembles contemporary regulatory thinking in areas ranging from data protection to financial services and anticipates future scrutiny rather than reacting to it after the fact.

Why This Matters Beyond AI

Although the report is framed around AI, its implications extend beyond artificial intelligence. At its core, the document is about data-intensive technologies and the institutional discipline required to use them responsibly. This is particularly relevant in climate and energy sectors, where data is increasingly granular, continuous, and meaningful.

As an example of data collection methodologies, smart meters are often discussed as hardware infrastructure or IoT, the Internet of Things. In reality, their value lies in what happens with the data after it is collected.

The Smart Carbon Meter from Carbon Credits Marketplace is a valid example. The data collection methodology typically involves high-frequency consumption information and long-term aggregation for dMRV (Digital Measurement, Reporting, and Verification), as well as the ability to forecast and track both emission trends and compliance.

From a governance perspective, this places the Smart Carbon Meter data firmly in the high-value data category, even where it does not strictly fit traditional definitions of personal information.

Therefore, the Queensland report's emphasis on data governance is directly relevant. It highlights the importance of data quality, provenance, integrity, security, and lifecycle management, underscoring that “data ensures trust, integrity, and quality as the foundation for AI systems to function.” The same is true for carbon accounting and emissions reporting.

Accountability, Not Automation

One of the most legally resonant themes of the report is accountability. It is repeatedly emphasized that the accountability for AI-enabled services cannot be delegated to the technology itself. The governance framework defines explicit roles, including responsible officials, strategy officers, data governance officers, and assurance functions, all designed to maintain a clear line of sight between organizational leadership and system outcomes.

A Quiet but Important Lesson

The most important lesson from Governance in the Age of AI is also the quietest. Systems built with governance in mind are more likely to gain trust, withstand regulatory changes, and support future analytical capabilities without costly redesigns. Those that do not may find themselves limited not by the law, but by their own lack of preparedness.

As the report itself notes, this work represents “a snapshot in time,” offered as a contribution to an evolving conversation. That conversation, about how data, technology, and governance intersect, is becoming increasingly urgent. And it is one that extends far beyond AI, to the heart of how we measure, manage, and regulate the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Source: GSQ (2025), Governance in the Age of AI: Preparedness and Responsible Leadership, October 2025.

Comments